Summary:

Chapter 9 is the first of seven chapters dedicated to one of the key “genotypes” presented in this book: that dedicated to “pop” music. The chapter begins with an aesthetic and sociological review of “pop music”, along with an offering of ten reasonable touchstones for this species. It then proceeds to the main thrust of the chapter: the unwinding of the historical and then musicological details behind the five “hits” for Subject 1, a devotee of the pop species. These five (four in the book, one on the website only) are: Taylor Swift’s “You Belong With Me”, Elle King’s “Ex’s & Oh’s”, Creedence Clearwater Revival “Proud Mary”, Michael Bublé’s “Georgia” (website only), and Lin-Manuel Miranda’s “It’s Quiet Uptown” from the musical Hamilton . The chapter closes with a range of potential candidates for addition / future hits for Subject 1, based on proximity on various levels to the five seeds.

Supplements:

- Page 306

( Presentation of 5th “hit” discussed for Subject 1: Michael Bublé’s “Georgia” ):

The following is the full discussion of the 5th song of the pop genotype, Michael Bublé’s “Georgia”, heard on the way home from work. It was excluded from the main text and delimited to the website only:

The Ride Home: Bublé’s “Georgia on My Mind”

Michael Bublé’s “Georgia on My Mind” reveals demonstrably that Subject 1’s taste for pop music lies on the eclectic side, extending even beyond the normal confines of popular music today (rock, country, hip hop, etc.). As a revival of a 1930 Tin Pan Alley jazz song, one can certainly point to non-pop elements here. And yet, Bublé’s “Georgia” does check off several boxes befitting the standard definition: commercially successful, slickly produced, accessible, and neatly packaged for a broad consumer market—even if its raw materials stem from a bygone era. This tension, indeed, shows the challenges of relying on genre labels to define music, and the risk of attempting to pigeon-hold someone’s musical genotype.

Background

Michael Bublé was born in 1979 in British Columbia, Canada, and like Swift and King, dreamed of a career as a superstar singer—from age 2, no less. Yet, unlike his female counterparts, Bublé was not drawn to contemporary rockers like Guns N’ Roses and Bon Jovi nor pop icons like George Michael and New Kids on the Block, but instead artists of yesteryear like Frank Sinatra and the Mills Brothers. Something in those old songs resonated with the young singer, both lyrically and musically—by his teens, this had become his music. Bublé’s fascination with “old time” songs, by the way, underscores how our personal musical taste is not formed solely by the dominant sub-culture around us, but also by the unique callings of our own personality; we’ll explore this much more in Interlude G. Bublé’s chances of becoming a star via the Great American Songbook were not great in the early 2000s, though there was some precedent with artists like Harry Connick and Rod Stewart. Bublé’s pop market success, however, broke the mold.

In 2003, Bublé met legendary producer David Foster (Celine Dion, Whitney Houston), who agreed to produce his first, self-titled album in 2003 . It gained marginal success, but its follow-up, It’s Time (2005) became a breakout hit: with glossily produced remakes of standards like “Feeling Good” and “The More I See You”, the album reached No. 7 on the Billboard Top 200. His next release, Call Me Irresponsible (2007) made Bublé a star—reaching No. 1 on the Top 200 and earning huge sales internationally. With it, Bublé and Foster hit upon a winning formula: a set of slinky 1930s-60s jazz standards interspersed with a few pop/rock classics, and 1 or 2 original songs in the pop or “adult contemporary” space. The pattern has served them well, with 4 more albums—including 2009’s Crazy Love —reaching No. 1 on the pop charts. His most recent album, To Be Loved (2013), however, shows signs of an even more decided pivot in the pop direction—not unlike Swift. It will be interesting to see what he displays on his next release.

Bublé’s commercial fame, moreover, can be seen as part of larger nostalgic zeitgeist in the past decade or so, with a growing number of jazz-pop artists like Norah Jones, Jamie Cullum, and most recently Landau Eugene Murphy, Jr. (winner of America’s Got Talent in 2011) gaining success in both the jazz and pop sector. If nothing else, it suggests that there is something intrinsic—musicologically—in these old songs that keeps the public’s taste coming back for more.[1]

Analysis

“Georgia on My Mind” stems from Crazy Love— which won the Grammy for Best Traditional Pop Vocal Album in 2009. This 1930 standard by Hoagy Carmichael and lyricist Stuart Gorell is, of course, most famously associated with the 1960 recording by Ray Charles.[2] Bublé’s vocal performance is more decidedly pop inflected. We hear this in his overall intimate vocal inflection, reminiscent of pop/R&B artists like Brian McKnight; it is also heard in the occasional melisma (ornate vocal run)—such as that leading into the last A section: from “Oh, I, Georgia” (Figure 9.W1):

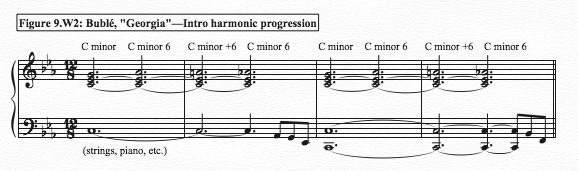

Structurally, “Georgia” fits neatly into the 32-bar AABA Tin Pan Alley song template (see Chapter 6), to which Bublé’s version largely conforms. The only deviations occur in the Intro and “Outro”: instead of starting and closing with typical progressions in the tonic (here Eb Major), Bublé’s version presents, as bookends, the initial chord progression of the B section, in the relative minor (C minor)—with it’s rise from the 5th to the minor 6th to the major 6th above the root of the chord, reminiscent of the “James Bond Theme” (Figure 9.W2) :

Bublé’s vocal is not overtly gospel-inflected, as is the Ray Charles version; and yet, the overall musical style here offers a quasi-gospel tinge, via its slow (60 BPM), bluesy, and 8th note triplet rhythmic feel. This is particularly the case in the piano accompaniment, with its prominent fills. Otherwise, the orchestration harkens back to the 1950s and 60s arranging style of Nelson Riddle (e.g., on ballads sung by Frank Sinatra and Nat King Cole)—with a full string orchestra, French horns, percussion, and harp, along with jazzy bass and drums. The strings offer occasional light counterpoint, but generally provide simple chordal accompaniment. The harmony largely sticks to the traditional, diatonic jazz chord progression of the original—with only occasional chromatic excursions, such as at the start of the 3rd A section.

Most dominant to the listening experience, though, is indeed Bublé’s vocal: beyond the occasional Mariah Carey-esque vocal runs, the recording is striking for his smooth, breathy vocal timbre—as well as the dramatic contrast created between the low-register of the opening AAB, and the emotionally-charged rise to the highest part of his range in the final A, before dropping back down for a quiet, gentle close.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] More details on Bublé’s biography can be found on the Wikipedia and All Music websites.

[2] For background on Carmichael’s song, see Sudhalter, Richard M. Stardust melody: the life and music of Hoagy Carmichael . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003: 136ff; on Ray Charles’ rendition, see Lydon, Michael. Ray Charles: Man and Music . London: Routledge, 2004: 181ff.

- Page 310

( More on the commonly used I-V-ii-IV chord progression ):

This chord progression is not as common as I-V-vi-IV (e.g., “Let it Be”), but is found in a good number of pop/rock songs. These include R.E.M.’s “It’s the End of the World As We Know It”, Beyoncé’s “Irreplaceable”, Katy Perry’s “Hot and Cold”, and Andrea Bocelli’s “Time to Say Goodbye”.

- Page 313

( More on Elle King’s personal background ):

More recently, King has opened up about her personal and psychological challenges; see, for example, Rendon, Christine. “’It felt like my life was over’: Elle King talks seeking treatment…” Daily Mail , July 2, 2017.

- Page 315

( More on the relationship between John Fogerty and Saul Zaentz ):

The contentious relationship was grounded on an admittedly unfair recording deal, in which Zaentz denied the band any publishing ownership. Fogerty’s antagonism for Zaentz—articulated, for example, in the songs “Mr. Greed” and “Zaentz Can’t Dance” (forcibly changed to “Vanz Can’t Dance”) from Fogerty’s Centerfield album (1985)—would consume Fogerty for years, even after the former’s death in 2014.

- Page 316

( More on the origins of “Proud Mary” and Fogerty’s experiences in late 1960s ):

Fogerty’s intent to celebrate his release from the National Guard with “Proud Mary” is suggested, for example, in the lyric “Left a good job in the City…” and documented in Fogerty’s interview on the “Pop Chronicles” radio series, produced on radio station KRLA-am (Los Angeles), narrated by John Gilliand in early 1970. As Joel Selvin wrote on the liner notes for the album’s 40th Anniversary reissue (2008), the song’s opening riff was improvised during a show at San Francisco’s Avalon Ballroom, and compiled in the studio from various song fragments.

- Page 319

( An observation on Miranda’s comment about “folder in my brain” ):

By Miranda’s quote (that Latin music, pop, hip hop, and Broadway “in the same music folder in my brain”), one notes the bemusing parallel between Miranda’s characterization of distinct musical genres and the trait-based categories discussed in Interlude C—although it is unlikely that the reference was explicit on Miranda’s part.

- Page 320

( More on the origins of Hamilton at the Obama White House ):

The White House event was entitled “An Evening of Poetry, Music, and the Spoken Word”, on May 12, 2009. Miranda presented “Alexander Hamilton” with the musical’s later music director / orchestrator Alex Lacamoire on piano. A video of the presentation can be found on YouTube.

- Page 320

( More on Miranda’s approach to chronicling the life of Alexander Hamilton ):

Some writers have noted Miranda’s occasional factual inaccuracies and oversights with regard to Hamilton’s portrayal in the musical—including overstating his progressive stance toward slavery and other character issues. As Chernow himself notes, “[Miranda] tries first to stick to the facts, and if he has to deviate from the facts I have found that there is always a very good reason for him doing it. I said to him, ‘Do you want me to tell you when I see historical errors?’ And he said, ‘Absolutely. I want the historians to respect this.’” (Mead, “All About the Hamiltons”)

- Page 320

( More on Miranda’s use of and approach to rap music ):

A detailed and interesting review of Miranda’s rap techniques in Hamilton , as relates to those used by other hip hop artists—e.g., Lauryn Hill of the Fugees, Big Pun, Rakim, Nas, and Kendrick Lamar—is found in Eastwood, Joel, and Erik Hinton. “How does ‘Hamilton’, the non-stop, hip hop Broadway sensation tap rap’s master rhymes to blur musical lines?” The Wall Street Journal , June 6, 2016. Among the techniques discussed are consonance, assonance, rhyme weaving, and West Coast influence.

- Page 320

( More on Miranda’s use two- and four- measure chordal patterns in Hamilton ):

By means of my informal tally, thirty of the forty-six numbers in the show involve a substantial or commanding use of looped chordal patterns—whether as two- or four-measure repeating formulae, or via an extended pedal point.

- Page 321

( More on Miranda’s comparison of Alexander Hamilton and Tupac Shakur ):

Hamilton reminded Miranda of Tupac Shakur; Miranda particularly admired “Brenda”: “a verse narrative about a twelve-year-old girl who turns to prostitution after giving birth to her molester’s child. Shakur was also extremely undiplomatic, publicly calling out rappers he hated. Miranda recognized a similar rhetorical talent in Hamilton, and a similar, fatal failure to know when enough was enough.”

- Page 321

( Further examples of “Alexander Hamilton” chord progression songs ):

Other songs using the “Alexander Hamilton” chord progression are: “Winter’s Ball”, “Guns and Ships”, “What’d I Miss”, “The Adams Administration”, and “Burn”. See Howard Ho’s “How Hamilton Works” video series for further discussions in this regard.

- Page 321

( Examples of non-loop songs in Hamilton ):

Among the non-loop based songs include “The Story of Tonight”, “The Schuyler Sisters”, “You’ll be Back” (and its later incarnations, all sung by King George III), “Hurricane”, and “Blow Us All Away”.

- Page 321

( Examples of Broadway quotations in Hamilton ):

Among the Broadway quotations include three listed in the actual Playbill program: “Nobody Needs to Know” from Jason Robert Brown’s The Last Five Years (in “Say No To This”); “The Modern Major General” from Gilbert & Sullivan’s The Pirates of Penzance (in “Right Hand Man”); “You’ve Got to Be Carefully Taught” from Rodgers & Hammerstein’s South Pacific (in “My Shot); others include “Sit down, John” from Sherman Edwards’ 1776 (in “The Adams Administration”); and “The Situation is fraught” from Stephen Sondheim’s A Funny Thing Happened On the Way to the Forum (also in “My Shot”).

Principal Bibliography:

Simon Frith, “Pop Music,” in The Cambridge Companion to Pop and Rock (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001)

Simon Frith, Taking Popular Music Seriously: Selected Essays (London: Routledge, 2007)

Rolling Stone , Artists: Taylor Swift (2008)

Hank Bordowitz, Bad Moon Rising: The Unauthorized History of Creedence Clearwater Revival (Chicago Review Press, 2007)

Rebecca Mead, “All About the Hamiltons,” New Yorker , February 9, 2015

Michael Bublé and Elle King entries on Wikipedia and All Music Guide

External Links:

"Popular Music" (Encylopaedia Britannica)