Chapter 15 is the seventh and final chapter dedicated to one of the key “genotypes” presented in this book: that dedicated to Western classical music. The chapter begins with a highly abbreviated historical and etymological gloss of classical music, along with an offering of ten reasonable touchstones for this species. It then proceeds to the main thrust of the chapter: the unwinding of the historical and then musicological details behind the five “hits” for Subject 7, a devotee of the classical music species. These five (four in the book, one on the website only) are: the opening movement, “O Fortuna” from Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana ; the opening Allegro from Antonio Vivaldi’s Concerto for Four Violins, Op. 3, no. 10; the second movement, Allegretto, from Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony no. 7 in A, Op. 92; the Overture to Leonard Bernstein’s Candide ; and the third movement, Sicilienne, from Gabriel Fauré’s Pelléas et Mélisande, Op. 80. The chapter closes with a range of potential candidates for addition / future hits for Subject 7, based on proximity on various levels to the five seeds.

Supplements:

- Page 542

( Presentation of 5th “hit” discussed for Subject 7: the opening movement, “O Fortuna” from Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana ):

The following is the full discussion of the 5th song of the classical genotype, the opening movement, “O Fortuna” from Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana , heard on the way home from work. It was excluded from the main text and delimited to the website only:

A Morning Walk: Carl Orff’s “O Fortuna”

Carl Orff’s “O Fortuna”, from Carmina Burana is the most explicitly “popular” of the 5 classical works favored by Subject 7—thus another ideal candidate for a classical “touchstone”. Indeed, it is yet another viable “touchstone”—apt to be recognized even by those who generally dislike classical music. This is in large part due to the enthusiastic embrace the movement has received in Hollywood, starting with its effective use in the 1981 film, Excalibur— played whenever King Arthur rides into battle with his Knights of the Roundtable.[1] Since then it has appeared in over a dozen films and film trailers, perhaps most famously in Oliver Stone’s 1991 film The Doors (during one of Jim Morrison’s drug-induced episodes), along with numerous TV shows, commercials, video games, and YouTube videos.[2] This ardent embrace has led some writers to call “O Fortuna” the “most overused piece of music in film history”, as well as the “Big Mac of classical music”.[3] However, its pop status has seemingly had little effect on the work’s esteem among classical aficionados—by virtue of how often it is programmed by major orchestras in the US and Europe.

Background

Given the overwhelming success of “O Fortuna”, it is rather surprising that Carmina Burana is the only work of Carl Orff (1895-1982) to have gained broad success even among classic music fans—most of whom would be hard-pressed to name a single other work by the composer.[4] As such, Orff may be considered a sort of classical “one-hit-wonder”, joining composers like Paul Dukas ( The Sorcerer’s Apprentice ) and Engelbert Humperdinck ( Hansel and Gretel ) in this dubious distinction. Orff was born in Munich and initially fell under the predictable spell of fin-de-siècle composers like Richard Strauss, Claude Debussy, and Arnold Schoenberg—thus embracing a musical language defined by advanced harmonic chromaticism.

In the 1920s, however, two influencing factors would lead to dramatic shifts in Orff’s musical style: his encounter with music of the late Renaissance / early Baroque and a newfound passion for the language and culture of classical antiquity. Significantly, Orff organized a staged production of Monteverdi’s 1607 opera Orfeo (translated into German) in 1923, in what may be considered a pioneering event in the “early music” movement. His personal discovery of the Latin poetry of Catullus (d. 54 BC) then led to two choral settings ( Catulli Carmina , 1930-31) that display a starkly more restrained style—one that would find more mature expression in works like Carmina Burana (1936-37). These forces (“early music” and classical antiquity) would continue to impact Orff’s compositional output, particularly in a series of grand theatrical works: Antigone (1941–9), Prometheus Bound (1963-67), and De Temporum Fine Comoedia (Play of the End Times, 1962-72).

As is the case today, however, Orff’s only significant compositional success in his lifetime came with Carmina Burana , first produced in Frankfurt in June 1937. This, of course, was during the height of Nazism, and questions of Orff’s tolerance of Nazi ideology have long dogged his biography. To be sure, Orff was never a member of the Nazi party, nor did he espouse any explicit support thereof; in fact, Carmina Burana was condemned as decadent and “incomprehensible” by Herbert Gerigk, an influential mouthpiece of Nazi propaganda. And yet, other German critics praised the premiere, and the work quickly became a favorite of Germany and the Nazis. At a minimum, therefore, Orff seems to have been guilty of opportunism, not above vigorously promoting his music during the height of Hitler’s dark reign.[5]

Beyond composition, incidentally, Orff is well known for his pioneering work in music pedagogy—through his Schulwerk (school work) approach.[6] In collaboration with gymnast Dorothee Günther and educator Gunild Keetman, Orff developed a unique strategy based on the concept of “elemental” music—emphasizing the “basic” building blocks of art: tone, movement, improvisation, text, and theater. The Schulwerk approach—also called the Orff Approach—emphasizes a child’s natural instincts to play and make music, teaching concepts by “doing” them. It is actively embraced even today, such as via the American Orff-Schulwerk Association.

Analysis

Carmina Burana is the name given to a manuscript of poems and plays compiled in the 11th-13 th centuries at a Benedictine monastery in Bavaria, Germany; the name means “Songs of Beuern”—an abbreviation of Benediktbeuren, the village containing the monastery where the manuscript was re-discovered in 1803. The collection is famed for its bawdy and satirical texts—mainly in Latin, but also in Middle High German and Provençal—written by a group of university-educated clergy, often privileged yet bored and disgruntled, called Goliards.[7] With the help of a philologist friend, Michel Hofmann, Orff assembled 24 poems from the collection into a libretto of what he called a “scenic cantata”. In contrast to the traditional concert format used today, Orff’s initial intention was that the work be fully staged with sets, costumes, dance, dramatic action, and “magic images.”[8]

The complete, hour-long work is scored for large orchestra (including two pianos), 3 choruses, and 9 vocal soloists. Its 24 movements are divided into 3 principal sections, along with a prologue and finale.

The famous opening movement, “O Fortuna”, likewise returns at its closing one. This reflects a basic premise of the work as a whole—echoing the famous front-page image from the Carmina Burana manuscript: the Wheel of Fortune. The Roman goddess Fortuna, maintained high currency throughout the Middle Ages—not least through the weighty influence of Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy (523 AD), where this deity embodies the capriciousness of fate as an inevitable extension of Divine Will. Medieval composers such as Machaut and Phillippe de Vitry set numerous texts related to Fortuna, perhaps most famously in the satirical Roman de Fauvel .[9] Orff too seizes upon the image of a powerful and vengeful Fortuna, and especially her Wheel of Fortune, not only to guide the cyclic recurrence of “O Fortuna”, but also to shape the overall progression of textual themes: from the pleasures of life and love to their inevitable sorrows, and round-and-around again.

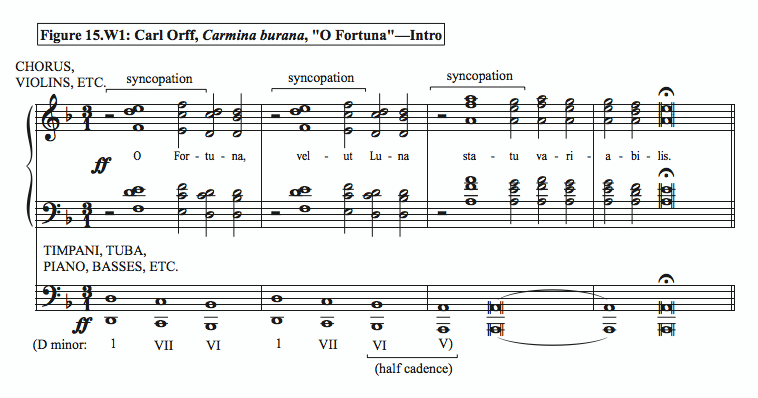

It is this awed, yet spiteful reverence for Fortuna—the “empress of the world”—that likewise explains the “epic” grandeur that Orff adopted in his musical setting of “O Fortuna”. The majesty is heard from the very onset via a series of slow and imposing fortissimo chords—with each of its three syncopated phrases initiated with a booming unison downbeat (Figure 15.W1):

The chords proceed as a descending diatonic progression in D minor, from the tonic to a half cadence on A. And yet, the absence of a major 3rd (C#) on the cadential chord suggests more a modal (D Aeolian) orientation than a tonal one—something to be borne out as the movement continues. Further, the step-wise, declamatory (one note per syllable) and homophonic (all voices moving in block together) choral melody in this “Intro” heralds the sober musical style that will define the movement—and much of the complete Carmina Burana —as a whole.

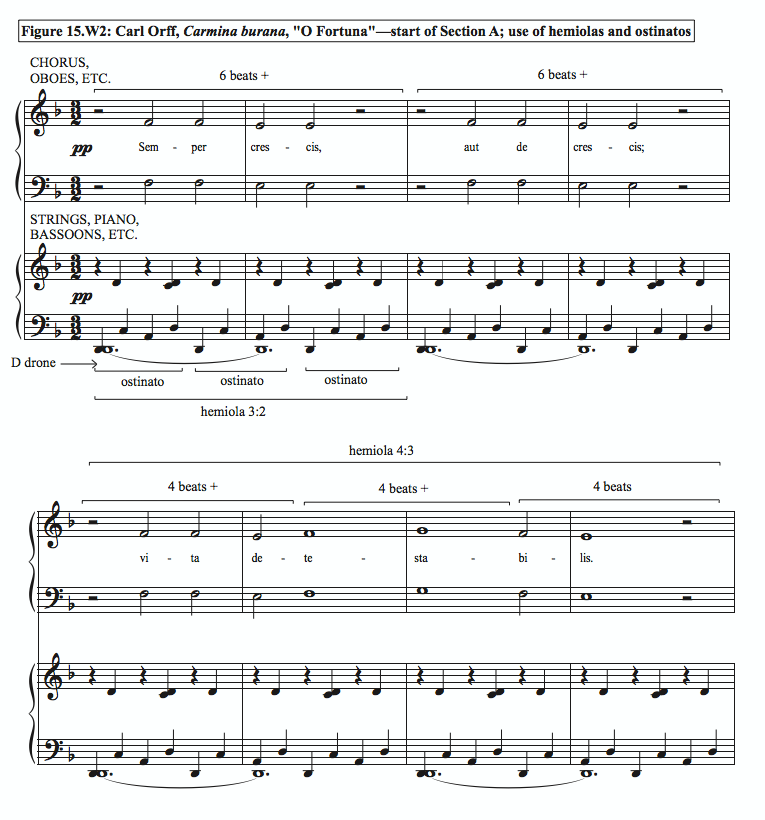

Beyond this melodic chordal style, the listening experience of “O Fortuna” is dominated by a few other musicological factors once the main, faster section begins: at the line “Semper crescis, aut decrescis” (Ever waxing and waning). First among these is a near-continual drone or pedal point, on D. Orff’s use of such an austere harmonic technique imparts to “O Fortuna” a rather “timeless” effect—neither modern nor ancient. Indeed, many of the 24 movements of Carmina Burana utilize a drone to undergird its discourse—at times punctuated with step-wise cadences (e.g., the frequent bVII-I cadences in “Veris leta facies”). The medieval origins of the libretto, informed by Orff’s own study of “early music”, undoubtedly served as inspiration for the wide adoption of the drone technique. Specifically, the D drone is intoned by the low strings, French horns, bassoons, pianos, and—in the fortissimo 2nd half—trombones. In the short closing “coda”, where the harmony shifts to D major, the drone is punctuated by periodic bVII-I “cadences”, from C to D.

Likewise dominant to the listening experience of “O Fortuna” is its steady, driving rhythm. The meter is rather unusual, and is one often used in transcriptions of Renaissance choral music: 3/2, meaning 3 beats per measure, where each beat is a half note. However, Orff does not here present a simple triple-based rhythm. Instead, most of the movement’s consistent 8-bar phrases (24 beats) are divided into a compound structure of 6+6+4+4+4. You may recognize that the latter part of this structure is a hemiola (4-against-3), which is then amplified via another dominant technique used by Orff: the ostinato. These repeating figures in the cellos, violas, and bassoons are used as accompaniment throughout, and generally in a syncopated, hemiola fashion—as repeating patterns of 4 quarter notes, creating cycles of 3 groups every 2 measures. The result is a kind of bubbling rhythmic engine that propels the steady, declamatory choral melody with pregnant energy (Figure 15.W2):

It is the perpetual use of ostinatos in “O Fortuna” (as in much of Carmina Burana ), incidentally, that links Orff’s music with that of Igor Stravinsky—perhaps the most influential composer of the early 20 th century. In such “Russian period” works as The Firebird (1910), Petrushka (1911), the Rite of Spring (1913), and Les Noces ( The Wedding , 1917), Stravinsky permeated his own musical discourse with overlapping ostinatos. To be sure, Stravinsky’s ostinato usage was often considerably more complex rhythmically, and generally set within a chromatic (poly-tonal) harmonic framework—quite distinct from Orff’s more straightforward approach. Still, many writers have linked Carmina Burana with Stravinsky’s Les Noces in particular—not only through its ostinato technique, but also for the use of the chorus, its heavy percussion, and its “primitive” driving rhythm.[10]

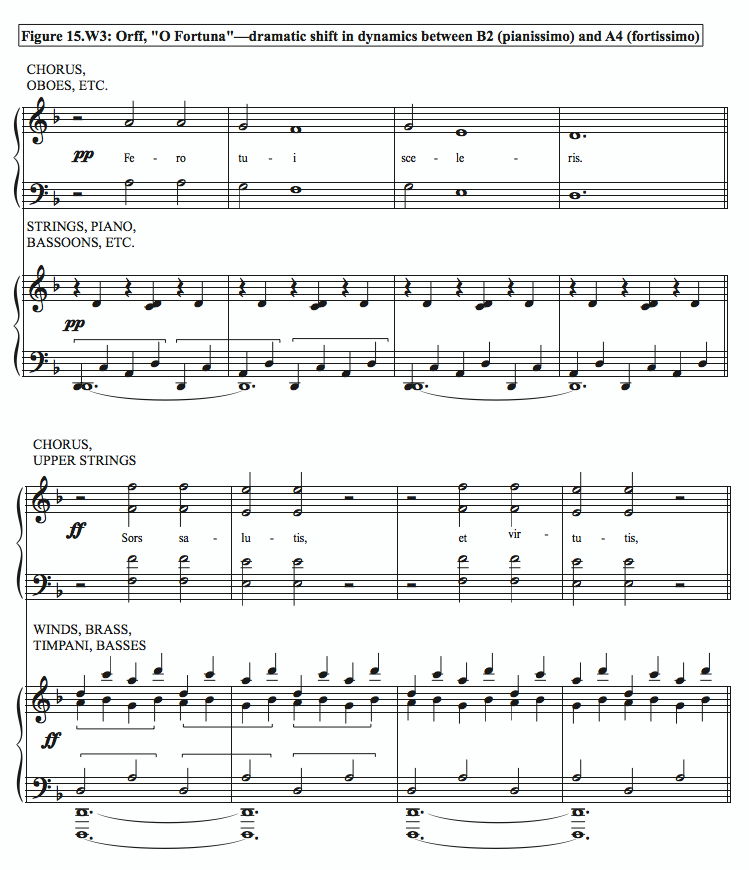

Finally, as already suggested in Chapter 6 (see Figure 6.8), the listening experience of “O Fortuna” is defined by a bit of sonic drama rarely matched in music history: that shift from pianissimo to fortissimo at the halfway point: at the line “Sors salutis” (Fate is against me). What makes this moment so effective is not just the sudden change of dynamics, but also the fact that Orff deliberately limits the variety of musical material before and after the shift. As such, he delivers the shift to fortissimo just at a point where the listener would otherwise expect yet another, pianissimo repetition; a fuller sense of the shift is shown in Figure 15.W3:

This economy of material can best be explained with a little formal schema:

Intro—A1—A2—B1—A3—A4—B’—B2–( dynamic shift) –A4—A5—B3—B’’—Coda

As this schema shows, Orff in essence alternates just 2 sections (A and B), which are themselves rather repetitive: each consists of 3 short phrases, where the first 2 are repeated (A = a-a-b; B = c-c-d). Indeed, B is itself a sort of variation of A (sounding a 3rd higher), and the melodies are simple, as noted above. As a result, even after a single hearing, the listener has internalized the musical discourse and has gained some expectancy as to the formal trajectory. Thus, when Orff “suddenly” shifts the same basic material up and octave, expands the orchestration, and explodes the dynamic level, the experiential impact is palpable. Is it not?

Orff’s effective use of dynamics, moreover, is a potent example of a key aesthetic shift in 20 th century classical music, as we discussed in Chapter 7: from “primary” parameters (melody, harmony, and rhythm) to “secondary” ones (tempo and dynamics). At any rate, it is likely that this now-famous dynamic drama in part accounts for the “hit” status of “O Fortuna” by Subject 7—as by so many others.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Excalibur also makes effective use of three other “warhorses” of the classical repertoire—all by Richard Wagner: “Siegfried’s Funeral March” from Götterdämmerung (Part IV of the Ring Cycle ), the “Prelude” from Tristan und Isolde , and the “Prelude” to Wagner’s final completed opera, Parsifal .

[2] See the substantial list on Wikipedia’s “Carl Orff’s O Fortuna in popular culture” page. Some of these are quite entertaining—such as the “O Fortuna Misheard Lyrics” (“Gopher Tuna…”) video on YouTube, with nearly 8 million views!

[3] See, for example, Friesen, Eric. “Carmina Burana: The Big Mac of Classical Music?” Queen’s Quarterly 118, no. 2 (2011): 280-281.

[4] For more on the life and music of Carl Orff, see, for example, Fassone, Alberto. “Orff, Carl” Grove Music Online (2001); and Kowalke, Kim H. "Burying the past: Carl Orff and his Brecht connection." The Musical Quarterly 84, no. 1 (2000): 58-83.

[5] See Taruskin, Richard. “Orff’s Musical and Moral Failings.” The New York Times , May 6, 2001.

[6] See, for example, Orff, Carl. "The Schulwerk: Its origin and aims." Music Educators Journal 49, no. 5 (1963): 69-74; also Goodkin, Doug. "Orff-Schulwerk in the new millennium." Music Educators Journal 88, no. 3 (2001): 17-23. “Schulwerk”, in fact, began as a set of pedagogical compositions for students 12 to 22; although called “Musik für Kinder” (Music for Children), many of them are quite challenging.

[7] See, for example, Godman, Peter. "Rethinking the Carmina Burana: The Medieval Context and Modern Reception of the Codex Buranus." Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 45, no. 2 (2015): 245-286.

[8] The work’s complete title is: Carmina Burana: Cantiones profanæ cantoribus et choris cantandæ comitantibus instrumentis atque imaginibus magicis ("Songs of Beuern: Secular songs for singers and choruses to be sung together with instruments and magic images". For additional review of the work from a musical and theatrical standpoint, see for example, Steinberg, Michael. "Carl Orff: Carmina Burana." Choral Masterworks: A Listener's Guide (2005): 230-242; and Stein, Jack M. " Carmina Burana and Carl Orff." Monatshefte (1977): 121-130.

[9] See, for example, Wathey, Andrew. “Fauvel, Roman de.” Grove Music Online (2001); Zayaruznaya, Anna. "‘She Has A Wheel That Turns…’: Crossed And Contradictory Voices In Machaut's Motets." Early Music History 28 (2009): 185-240; also Dillon, Emma. Medieval Music-Making and the Roman de Fauvel . Vol. 9. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

[10] Taruskin. “Orff’s Musical and Moral Failings”: “’Carmina Burana’ abounds in out-and-out plagiarisms from ‘Les Noces.'”

- Page 547

( More on Italian word “estro” ):

The Italian word “estro” could alternately be translated as “sting”, “stimulus”, or “frenzy”.

- Page 548

( More on the Amsterdam-based publisher Estienne Roger ):

Roger, significantly, was also the publisher of perhaps the second most influential collection of instrumental music of the eighteenth century—Arcangelo Corelli’s concerti grossi Opus 6 (1714); see Landon. Vivaldi : 42.

- Page 549

( More on a common criticism of Vivaldi’s music ):

Stravinsky once famously quipped that Vivaldi “didn’t write 500 concertos; he wrote the same concerto 500 times”; even more caustically, musicologist and pianist Charles Rosen wrote: “he began 500 concertos and never achieved anything in them. So, he kept trying over and over again without ever quite succeeding.” Cited in Bixer, “On the Rating of Composers” (see n. 638)

- Page 552

( More on Vivaldi’s approach to the ritornello structure ):

Vivaldi also begins with an episode instead of a ritornello in the first of the Opus 3 concertos (No.1 in D).

- Page 554

( More on Beethoven’s family lineage ):

Beethoven’s lineage was also common: the particles van and von both mean “of” or “from”, yet only the latter designated German nobility—though at times the composer would fuel confusion about his own status. His common lineage would in turn place limits on his prospects both romantically and legally, as when he painstakingly fought for custody of his nephew Karl, from 1815. See Solomon. Beethoven : 117; 297ff.

- Page 557

( More on the initial concert premiering Beethoven’s 7th Symphony ):

The benefit concert also included the premier of Beethoven’s orchestral “battle overture” Wellington’s Victory , largely seen as a novelty work today. However, its performance was chronicled by the orchestra’s first violinist, Louis Spohr, who reveals Beethoven’s eccentric conducting style: “At piano [soft] he crouched down lower and lower according to the degree of softness he desired. If a crescendo then entered he gradually rose again and at the entrance of the forte (loud) he jumped into the air…” See Steinberg, Michael. The Symphony: A Listener's Guide . Oxford: Oxford University Press, USA, 1995: 41.

- Page 558

( More on Beethoven’s use of the dactyl rhythm in the 7th Symphony ):

Solomon has connected the rhythm of the “Allegretto” (as with other works) with the composer’s fascination with antiquity—noting the link between this rhythm and the Greek poetic meter of dactylic hexameter: namely, a dactyl (long-short-short) plus a spondee (long-long). Solomon, Maynard. Late Beethoven: Music, Thought, Imagination . Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004: 109-113.

- Page 558

( More on the famous anecdote about Wagner dancing nonstop to the 7th Symphony ):

This perhaps apocryphal anecdote follows upon Wagner’s high praise of the work: “If anyone plays the Seventh, tables and benches, cans and cups, the grandmother, the blind and the lame, aye, the children in the cradle fall to dancing.”

- Page 560

( Further analysis detail of the “Allegretto”: on claims of it as a double variations ):

It is the partial repeat of the A major section (B) that has led some to describe the Allegretto” as a double variation—or better “alternating variation”, where two sections (A and B) alternate in successive variations. This was an oft-used formal procedure in the works of Franz Joseph Haydn, namely in his piano sonatas, string quartets, and symphonies (e.g., the Andante of his Symphony No. 90 : A—B—A’—B’—A’’—Coda). Beethoven likewise indulged in the form on occasion—as in the third movement of the String Quartet No. 15, Op. 132 (A—B—A’—B’—A’’). In the “Allegretto” of the 7th Symphony , however, the return of the B section (in A major) cannot, to my mind, be labeled a variation, but instead is but a partial reprise (the opening phrase c only) with a short extension of the concluding two bars that transition to the next A minor variation. It is true that the “Allegretto” alternates two contrasting sections, but as noted does so as part of an overall “variations rondo” form. In her detailed discussion, Elaine Sisman notes Beethoven’s deviation from Haydn’s model in the “Allegretto”, noting that the “second theme [is] varied less than the first.” Indeed, she calls it a “shortened reprise-like variation”, whereas I would remove the latter word—semantics, perhaps. See Sisman, Elaine R. "Tradition and transformation in the alternating variations of Haydn and Beethoven." Acta Musicologica 62, no. Fasc. 2/3 (1990): 176.

- Page 564

( More on Bernstein’s pedagogical identity ):

Bernstein’s pedagogical legacy endures today via his “Artful Learning” approach and philosophy, founded in 1992 and dedicated to using art—especially music—to enhance education more broadly.

- Page 565

( More on Candide’s mantra at the close of the operetta ):

As Candide states in in his penultimate line of the libretto: “What we wanted, we will not have. The way we did love, we will not love again. Come now, let us take what we have and love as we are.” There’s nothing left to do, that is, but to turn to a more practical approach to life—or in Voltaire’s words, “il faut cultiver notre jardin” (we must cultivate our garden). See also Smith. There a place for us : 112.

- Page 565

( More on Bernstein’s personal vision of the operetta, from his son Jamie ):

As Bernstein’s son Jamie writes: “Candide" is often referred to as Leonard Bernstein's valentine to Europe, because of the way he affectionately raided every European song and dance form he could think of in the process of composing the music. This score is the very definition of ‘pastiche.’ Here is an incomplete list of his sources: schottische, tango, polka, mazurka, Venetian waltz, English folk song, gavotte, barcarole, Neapolitan bel canto, Germanic chorale, coloratura —and even a 12-tone row, which Bernstein deliberately uses in a song about boredom!” From Jamie Bernstein’s lecture, “A Talk on Candide.” Cited on Jamie’s website.

- Page 567

( More on the ascending intervals in West Side Story and Candide ):

Indeed, each show begins by demonstrably announcing their respective ascending intervals: the ascending tritone in the “Prologue” of West Side Story , the ascending minor 7th in the “Overture” of Candide .

- Page 573

( More on “Glitter and Be Gay” ):

As Helen Smith notes, “Glitter and Be Gay” is “frequently labeled as a parody of the Jewel song, ‘ah! Je ris de me voir’, from Gounod’s Faust . Despite sharing subject and sentiment—jewels and the love of them—the two songs have little else in common.” Smith. There’s a place for us : 123.

- Page 574

( More on the Musipedia service ):

Musipedia, though a bit clumsy, enables one to input melodies in a number of way: by an external MIDI keyboard, FLASH piano, manual input using your computer, via contour, rhythm, with a microphone, etc. From my few attempts, the results were remarkably accurate, with numerous alternative suggestions—not only classical, but pop/rock, folk, etc.

- Page 575

( More on use of Fauré’s Pavane in film and TV ):

These include the 2010 film Ice Castles, and the 2015 TV episode of Mr. Selfridge .

- Page 578

( More on Fauré’s potential inspiration for Proust in In Search of Lost Time ):

Indeed, Fauré’s La Ballade, Op. 19 , for piano and orchestra (in its piano solo version), has been cited as a possible source of Proust’s “Sonate de Vinteuil, although Saint-Saëns’s Violin Sonata No.1 in D minor (1885)—though “the little phrase” of Vinteuil’s sonata has likewise been associated with violin sonatas by César Franck, Johannes Brahms, and (via reference by Proust himself) “the charming but ultimately mediocre phrase of a violin sonata by [Camille] Saint-Saëns, a musician I do not care for.”

- Page 578

( More on honors for Fauré toward the end of his life ):

Notable awards include the Grand-Croix of the Légion d’Honneur (1920) and a rare national tribute at the Sorbonne, where celebrated musicians played a number of his works before a crowd of dignitaries—somewhat ironic given the composer’s by-then pronounced deafness.

- Page 578

( More on Fauré’s influence on the Impressionist generation ):

Fauré had a pronounced influence on the harmonic and formal revolutions by Debussy and Ravel, despite his own overt criticism of the latter developments—noting in 1916, for example, that in comparison to the adventurous Impressionist and Cubist painters the “less daring composers [i.e., Debussy] were trying in their works to suppress sentiment and to substitute sensation , forgetting that sensation is in fact, a necessary preliminary to sentiment.” Cited in Nectoux. Gabriel Fauré : 497.

- Page 578

( More on Fauré’s influence on the 1920s Parisian school, Les Six ):

The members of Les Six likewise admired Fauré, although Poulenc specifically criticized Fauré’s conventional approach to orchestration; for example, he described Fauré’s orchestration of the opera Pénélope as a “leaden overcoat” and as “instrumental mud.” See Nectoux. Gabriel Fauré : 258.

- Page 578

( More on Fauré’s feud with Brahms ):

As an example, Fauré once reprimanded a piano professor at the Paris Conservatory—Alfred Cortot, who later founded the École Normale de Musique in Paris—for having the audacity of assigning a work by Brahms to his students.

- Page 580

( More on the profound influence of Goethe’s Faust on 19th century composers ):

Dozens of composers were drawn to this mystical tale, written in two parts: published in 1808 and 1831). Of medieval origins, Faust is the story of a scholar (Faust) willing to offer his soul to the devil (Mephistopheles) in exchange for transcendent knowledge. Musical settings range from direct excerpts (Schubert, Wagner, Mahler, Wolf) to concert adaptations (Schumann, Berlioz) to an orchestral “tone poem” (Liszt) to full-blown operas (Gounod, Arrigo Boito). All of these reveal Goethe’s “fantastical” play as a potent catalyst in the enhancement of musical expression via melodic, harmonic, formal, and instrumental innovation.

- Page 582

( More on the influence of Lefévre harmonic theories and innovations ):

More specifically, Lefévre adopted a conception of harmony—via the pedagogical approach of George Joseph (Abbé) Vogler in the early 19th century—as derived not from the root of a chord, but rather from the degree of the scale on which a “chord” is situated; the result is a more modal approach harkening to the Renaissance and early Baroque (e.g., Palestrina and Gesualdo). To an innovative mind like Fauré’s, then, this enabled a much more flexible approach to traditional tonal harmony, whereby 9ths, 11ths, “borrowed” 3rds, etc. could be conceived intuitively, and not necessarily as a radical break from tradition.

Principal Bibliography:

Daniel Heartz and Bruce Alan Brown, “Classical,” Grove Music Online

Alberto Fassone, “Orff, Carl” Grove Music Online (2001)

Susan Adams, Vivaldi: Red Priest of Venice (Oxford: Lion Books, 2010)

Claude V. Palisca, Baroque Music (Englewood Cli s, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1991)

Maynard Solomon, Beethoven (London: Schirmer Trade Books, 2012)

John Warthen Struble, The History of American Classical Music: MacDowell through Minimalism (New York: Facts on File, 1995)

Allen Shawn, Leonard Bernstein: An American Musician (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014)

Jean-Michel Nectoux, Gabriel Fauré: A Musical Life , trans. Roger Nichols (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004)

Walter Frisch, Music in the Nineteenth Century (New York: W. W. Norton, 2013)

External Links:

"Classical Music" (Encylopaedia Britannica)

Antonio Vivaldi (Encylopaedia Britannica)

Leonard Bernstein "Official" Website

Gabriel Fauré (Encylopaedia Britannica)