Summary:

Chapter 10 is the second of seven chapters dedicated to one of the key “genotypes” presented in this book: that dedicated to rock. The chapter begins with an aesthetic and sociological review of rock, along with an offering of ten reasonable touchstones for this species. It then proceeds to the main thrust of the chapter: the unwinding of the historical and then musicological details behind the five “hits” for Subject 2, a devotee of the rock species. These five (four in the book, one on the website only) are: Led Zeppelin’s “Ramble On”; Alabama Shakes’ “Don’t Wanna Fight”; Muse’s “Butterflies and Hurricanes”; Louis Prima’s “Just a Gigolo / I Ain’t Got Nobody”; and Lucinda Williams’ “Are You Alright?”. The chapter closes with a range of potential candidates for addition / future hits for Subject 2, based on proximity on various levels to the five seeds.

Supplements:

- Page 357

( Presentation of 5th “hit” discussed for Subject 2: Lucinda Williams’ “Are You Alright?” ):

The following is the full discussion of the 5th song of the rock genotype, Lucinda Williams’ “Are You Alright?”—heard as a relaxing way to wind down the day. It was excluded from the main text and delimited to the website only:

A Relaxing Close to the Day: Lucinda Williams

Lucinda Williams’ “Are You Alright?” returns to more expected musicological terrain for Subject 2’s rock hit parade, not least in comparison to the previous selection. At the same time, “Are You Alright?” confirms our increasing impression of Subject 2 as an eclectic rock fan, still principally at home with a groove-driven repeating chord pattern, but likewise happy with a more acoustic, folk-oriented approach—and especially as bedtime nears.

Background

Lucinda Williams was born in 1954 in Lake Charles, Louisiana, and spent much of her youth moving from one Southern locale to another—through Louisiana, Mississippi, and finally Arkansas—as her professor father moved from one university job to another. It is thus not a big surprise that her musical tastes run vividly to Southern rural styles such as country, folk, and acoustic blues. From her 1st album on the Smithsonian / Folkways label ( Ramblin’ on my Mind , 1978) to her 12 th and most recent album on her own label ( Ghosts of Highway 20 , 2016), Williams has pursued a distinctive blend between these rural styles and a tempered electric rock sonority and sensibility—akin to other Americana, alternative folk, or heartland rock artists like Bonnie Raitt, Emmylou Harris, and Lyle Lovett.[1]

In so doing, major commercial success has rather eluded Williams. This is not to say that her records haven’t sold: based on charts, she can claim 4 albums (of her last 5) that have reached No. 15 or higher on the Billboard Top 200—the highest being 2008’s Little Honey , which reached No. 9. But rather than “rock star”, a more apt description of her career status might be that of a “musician’s musician”: lauded by critics, admired by her colleagues (including well-known artists like Willie Nelson, the late Tom Petty, and Elvis Costello), and supported by a small but loyal fan base. And this appears to be just fine with Williams. In the early 1990s, she walked away from a prestigious contract with RCA records after they wanted to release pop-oriented re-mixes of her songs; and even after the release of her “breakthrough” album— Car Wheels on a Gravel Road (1998)—she jokingly sub-titled a keynote talk at the South by Southwest festival, “Why I Don’t Want To Be a Star”.[2]

Of course, it is those influential artists residing “under the radar” of commercial success who are the true heroes of rock music for many serious fans. Indeed, for hardcore aficionados, grand commercial success can all too easily dilute the authenticity of the music, and even prevent an artist from achieving aesthetic excellence or realizing the evolutionary potential of the style being pursued. As with fellow Americana singer-songwriter John Prine, moreover, Williams’ reputation is built not only on her own albums, but likewise on the regularity with which other artists have recorded her songs: well over a dozen have been covered by such singers as Nelson, Petty, Harris, John Mellencamp, and Mary Chapin Carpenter—whose version of Williams’ “Passionate Kisses” won the 2003 Grammy for Best Country Song. This is by no means to diminish the experiential power of Williams’ own recordings in mobilizing and inspiring her fans; her distinctive approach is undoubtedly a key factor. On the other hand, the fact that Williams resides comfortably in the “under the radar” category seems to pose no problem at all.

Analysis

“Are you Alright?” is the opening track of Williams’ 8th album West (2007). It is one of those “distinctive” recordings that has been critically acclaimed—for example, ranked as No. 34 in Rolling Stones magazine’s “Best Songs of 2007”—yet only marginally successful with consumers. However, it did gain a bit of extra-musical exposure by means of its appearance on a couple of TV shows— namely, House M.D. (2007) and True Detective (2014).

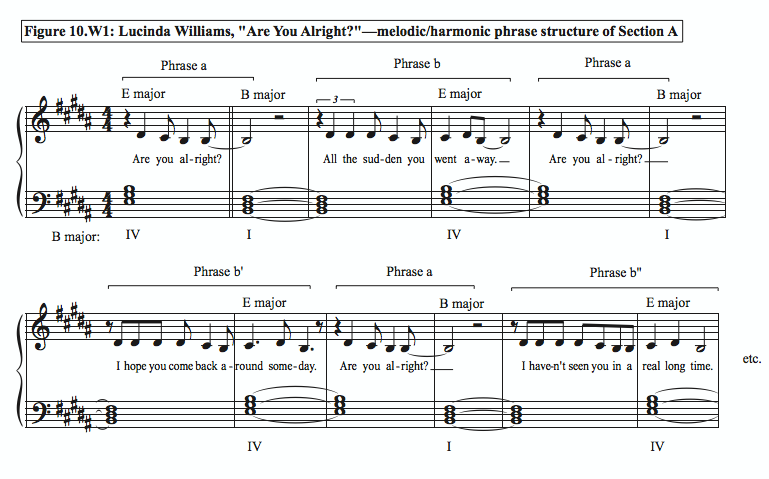

Like several of its predecessors in Subject 2’s “hit parade”, “Are You Alright?” employs a repeating 2-chord pattern for a majority of its discourse: in this case, a pivot between B and E, or I-IV, taking place within the context of a medium slow, mellow yet driving 4/4 groove. In the absence of a dominant 7th on either chord, however, the normal blues quality of this progression is rather subjugated. But most striking about the song is that this harmonic pattern is accompanied by a highly repetitive melodic / poetic pattern as well, where the phrase identity is consistently a-b; in each case the “a” motive (d#-c#-b-b) is set to the poetic refrain “Are you alright?” followed by a varied “b” line that specifies the singer’s concern about a former lover (Figure 10.W1):

As such, musically and poetically Williams creates a kind of mantra that somehow doesn’t become tiresome; it is yet another example of how powerful this harmonic progression of I-IV can be in locking and engaging our musical experience. Each pairing—4 measures, 2 per chord—is repeated 4 times to create a complete section: a Refrain or A section. After 16 bars, the A refrain is repeated, now augmented sonically by background vocals, and later by piano and B-3 organ—joining an otherwise standard Americana instrumentation of acoustic and electric guitars, bass, drums, and shaker.

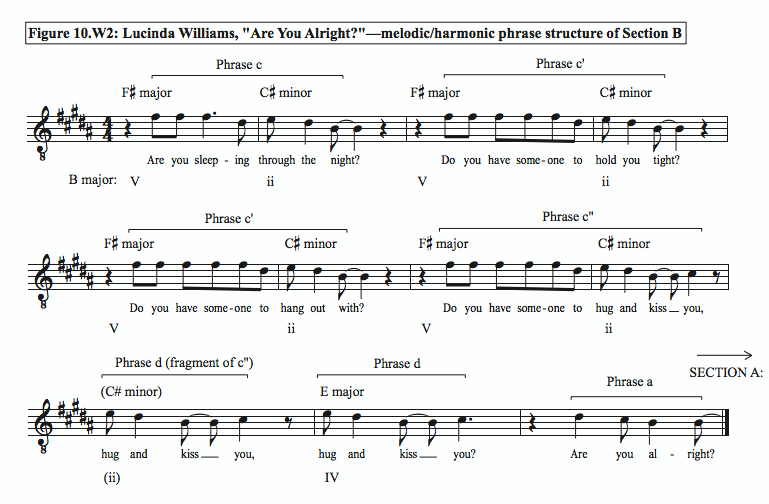

At that point, a B section is introduced that harmonically, rhythmically, and melodically / lyrically replaces the earlier pattern with a new one: a looping progression between F# and C# minor (V-ii), with 1 measure per chord—thus introducing a more animated harmonic rhythm (Figure 10.W2):

This pairing too repeats 4 times (total of 8 bars), followed by a 2-measure extension to E major that sets up a return to the B-E pivot, and an 18-measure guitar solo—consisting of a truncated mix of the A and B sections. At that point the entire form A—B returns vocally followed by an extended tag on the B-E pivot to end the song.

While the harmonic patterning and melodic refrain of “Are You Alright?” are the most striking musicological elements of the song, the actual listening experience is equally (if not predominantly) defined by the quality and persona of Williams’ vocals. Like other folk-related singers such as Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen, Williams does not have a technically potent voice, on par with Plant or Howard, for example; however, she does have very good intonation (staying on pitch) and a strong vocal personality. Her timbre is an interesting mix of gritty and breathy tones, while her low-key delivery (rather the opposite of Howard) lends a good dose of sincerity and power to her performance.

Undoubtedly, it is this mix of a mellow groove, derived from a 2-chord harmonic pattern, and a dynamic vocal performance that made “Are You Alright?” an ideal pick for Subject 2 to round out a busy day.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] More background on Lucinda Williams can be found, for example, in her interview with Jane Shilling: “Lucinda Williams Interview: ‘I’ve earned the right to say what I like’.” The Telegraph , May 25, 2013; see also her biography in Rolling Stone .

[2] Martin, Philip. The Artificial Southerner: Equivocations and Love Songs . Fayetville, AR: The University of Arkansas Press, 2001: 110-111.

- Page 361

( More on the decadence of Led Zeppelin in their heyday ):

Summarizing the decadent week spent at Hollywood’s Chateau Marmont hotel in May 1969 (girls, drugs, alcohol), for example, Cole writes: “Back in England, Zeppelin lived quite normal lives with storybook-like families or girlfriends. But the road—particularly Los Angeles—was becoming a place of excess.”

- Page 362

( More on the naming of the band Led Zeppelin ):

The most commonly accepted story (though not the only one) is that 2 years prior, in May 1966, Moon was at a recording session with Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones; when Page suggested the notion of forming a new band, Moon supposedly said that it would go over like a lead balloon.

- Page 362

( More on the other Led Zeppelin songs aligned with The Lord of the Rings ):

Songs with fairly overt reference include “Misty Mountain Hop” and “Battle of Evermore”; other songs with more possible connection include “Stairway” and even “Over the Hills and Far Away”. See Wall. When Giants Walked the Earth : 240-241.

- Page 364

( More on a possible link between “Ramble On” and “Bluebird” by Buffalo Springfield ):

Perhaps, indeed, this is deliberate: note that as the song is fading down, Plant sings: “can’t find my bluebird… I’d listen to my bluebird sing”—which perhaps is a reference to the Buffalo Springfield song; the two bands, after all, were both on Atlantic.

- Page 368

( A bit on Matt Bellamy’s father, and details on Muse’s reference to classical works ):

Matt’s father, George Bellamy, was also a working musician, having played rhythm guitar with the 1960s English instrumental group The Tornados. See also Hodgkinson, Will. “Matt Bellamy.” The Guardian , August 16, 2001. Examples of direct influence of classical composers on Matt’s songs, beyond “Butterflies and Hurricanes”, include “Space Dementia” (Rachmaninov), “I Belong to You” (Saint-Saëns), and “United States of Eurasia” (Chopin).

- Page 368

( More on Muse’s record company relationships ):

Since the band’s third album, Absolution (2003), the band has been signed with Warner Brothers Records.

- Page 371

( More on the Neapolitan 6th chord in music history ):

As noted, in music theory, the Neapolitan 6th chord is a major chord built on the bII degree of a minor key, generally presented in 1st inversion—thus a Db major chord voiced F-Ab-Db (the 6th between the F and Ab giving the chord the name) in C minor; typically it proceeds to the V7 chord in an authentic cadence, leading to the I chord; as such it is a chromatic replacement to the more diatonic iv chord. It was common in the Baroque era, but continued well into the 19th century among classical composers—including Rachmaninov (e.g., in his Andante of his 1st Piano Concerto ). It has also been used frequently in popular music, including the intro of The Beatles’ “Do You Want to Know a Secret”.

- Page 374

( A personal anecdote of the author regarding Louis Prima’s drummer ):

Dr. Gasser had the privilege of performing with drummer Bobby Morris, who even in his 70s could play his “Morris shuffle”, as it is called, at break-neck tempos.

Principal Bibliography:

Marc Woodworth, Robert Boyers, and James Miller, “Rock Music & The Culture of Rock: An Interview with James Miller,” Salmagundi 118/119 (1998): 206–23.

Mark Spicer, ed., Rock Music (New York: Routledge, 2016)

Mick Wall, When Giants Walked the Earth: A Biography of Led Zeppelin (London: Macmillan, 2010

Joe Rhodes, “Alabama Shakes’s Soul-Stirring, Shape-Shifting New Sound,” New York Times , March 18, 2015

Mark Beaumont, Muse: Out of This World (London: Omnibus Press, 2014)

Tom Clavin, That Old Black Magic: Louis Prima, Keely Smith, and the Golden Age of Las Vegas (Chicago Review Press, 2010)

Jane Shilling: “Lucinda Williams Interview: ‘I’ve earned the right to say what I like’.” The Telegraph , May 25, 2013

External Links:

"Rock Music" (Encylopaedia Britannica)

Alabama Shakes Official Website

Louis Prima Official (Fan) Website

Lucinda Williams Official Website