Summary:

Chapter 12 is the fourth of seven chapters dedicated to one of the key “genotypes” presented in this book: that dedicated to hip hop. The chapter begins with an aesthetic and sociological review of rap and hip hop, along with an offering of ten reasonable touchstones for this species. It then proceeds to the main thrust of the chapter: the unwinding of the historical and then musicological details behind the five “hits” for Subject 5, a devotee of the hip hop species. These five (four in the book, one on the website only) are: Snoop Dogg’s “Gin & Juice”; Kendrick Lamar’s “i"; Eminem’s “Lose Yourself”; Earth, Wind & Fire’s “Shining Star”; and Common & John Legend’s “Glory”. The chapter closes with a range of potential candidates for addition / future hits for Subject 5, based on proximity on various levels to the five seeds.

Supplements:

- Page 431

( Presentation of 5th “hit” discussed for Subject 4: Common & John Legend’s “Railroad” ):

The following is the full discussion of the 5th song of the hip hop genotype, Common & John Legend’s “Glory”—heard as a winding down before bedtime. It was excluded from the main text and delimited to the website only:

A Late-Night Spiritual Lift: Legend & Common’s “Glory”

John Legend & Common’s “Glory” helps Subject 4 close the day with a far mellower listening experience than that offered by the day’s previous “hits”. It does so first by reconciling the vocal nature of “Shining Star” with the rapping discourse of the opening 3 songs. It then combines, indeed heightens, the socio-political reflections found in Snoop Dogg and Lamar’s songs with the hopeful messaging of EWF’s entry. Indeed, the lyrics of “Glory” reinforce hip hop’s concern with the challenges and strivings of the African-American experience—referencing not only the famed Civil Rights march led by Dr. Martin Luther King across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama in 1965, but also the hopes aligned with today’s Black Lives Matter movement. Finally, in the embrace of “Glory”, we recognize in Subject 4 a musical genotype open to a broad spectrum of hip hop, including that element informed by collaboration with modern pop and R&B.

Background

“Glory”, as suggested above, is a rap / sung collaboration. The pairing of rapped verses with a sung chorus is certainly not a new trend in hip hop, going back to the realm’s earliest days—such as in “White Lines” (1983) by Grandmaster Flash and Melle Mel. As rap became mainstream, however, more and more prominent singers—especially in the R&B realm—began to welcome the opportunity to partner with “hot” rap artists. Each of the first three rappers in Subject 4’s “hit parade”, for example, has produced multiple of tracks in collaboration with the day’s top singers: Snoop Dogg with Pharrell and Katy Perry; Lamar with Alicia Keys and Taylor Swift; Eminem with Rihanna and Gwen Stefani, to name but a few. There’s even a Grammy Award category (since 2002) of “Best Rap/Sung Collaboration”—which both Eminem and Lamar have won. Experientially speaking, these collaborations satisfy a listening desire for both the rhythmic / messaging potency of a rap track and the intoxicating appeal of a well sung melody. The collaboration of rapper Common and singer John Legend on “Glory”, therefore, is just yet another example of this paired approach—albeit an unusually well celebrated one, having won a Grammy Award, Golden Globe, and an Oscar.

John Legend was born John Stephens in Springfield, Ohio in 1978. A precocious child, he graduated high school at age 16 and attended the University of Pennsylvania, turning down admissions from both Harvard and Georgetown. Although he studied English and African-American studies, Stephens had always been musical—singing in the local church choir from age 4, and studying piano from age 7. In fact, it was the palpable debt Stephens paid in his singing to the gospel roots of R&B that led poet and Kanye West collaborator J. Ivy to suggest his future stage name—telling him, “you sound like one of the legends”—which the singer eventually responded by professionally adopting the name in 2004. [1] While working with the university a cappella group, Legend caught a key break: being hired as pianist for R&B singer Lauryn Hill. A couple of years later, in 2001, Legend was hired to sing “hooks” to tracks by Kanye West, then an up-and-coming rapper; when, in 2003, West started his own label, GOOD (Getting Out Our Dreams), Legend became his first signed artist. Chart and critical success came immediately with their first partnered release, Get Lifted (2004), produced by West; it earned Legend 2 Grammy Awards, including for Best R&B Album, as well as for the hit single “Ordinary People”.

Similar levels of success came with Legend’s next two albums, Once Again (2006) and Evolver (2008)—which included the hits “Heaven” and “Shine”, among others. Along the way too came frequent collaborations with rap artists like Jay Z, OutKast, and the Roots, as well as with West himself. But it was his 4th GOOD release, Love in the Future (2013) that turned Legend into a megastar, principally by virtue of the international hit, “All of Me”—which rose to No. 1 on the Billboard Top 100. [2] Although Legend has occasionally had to play apologist for West’s frequent (and often egotistical) outbursts (“he says what he says, … but he’s one of the most important and prolific artists we have in the business”, Legend once said of West [3] ), the two have become a potent force in today’s hand-in-glove rapport between rap and R&B—a counterpart of sorts to the industry-shaking role played by producer Dr. Dre for rappers like Snoop Dogg and Eminem.

Common is the nickname of rapper, poet, actor, and activist Lonnie Rashid Lynn, Jr. Like his fellow-rappers in Subject 4’s “hit parade”, Lynn grew up in a gritty urban environment—namely, in the economically mixed black neighborhood of Avalon Park in Chicago’s south side, where he was born in 1972. Yet, like Legend, Lynn also grew up in a home that prized education—his mother is a well-regarded teacher and principal in the Chicago Public Schools. [4] By his teens, Lynn was writing rap lyrics under the name Common Sense (which for legal reasons he had to shorten to Common in 1994); he even formed a rap group, under the name CDR (including the now prominent rap producer No I.D.), which once opened for N.W.A.

Yet from his earliest songs, Common has displayed a penchant to tackle hot-button social and political issues—ranging from the alarming rates of HIV / AIDS among African-Americans to the plight of inner-city kids in his native Chicago to the broader black intellectual tradition of liberation philosophy, etc.; he even openly questioned the violent and misogynistic trends of hip hop, and especially West Coast gangsta rap, in his 1994 song “I Used to Love H.E.R.” (standing for “hearing every rhyme”) which sparked a feud with N.W.A.’s Ice Cube that had to be mediated by Louis Farrakhan. As he expressed in a 2012 interview, “If you have a microphone, you can help people; you can give them inspiration; you can raise awareness.” [5] Such “conscious rap”, as it is called, has earned him praise from African-American intellectual leaders like poet Maya Angelou and activist / philosopher Cornell West.

Along the way too, however, Common has produced several hit records, starting with Like Water for Chocolate (2000). Even greater success came in 2004, after he, like John Legend the year before, was signed to Kanye West’s GOOD label: their 2nd release, Finding Forever (2007), reached No.1 on the Billboard Top 200 and earned Common a Grammy. Like his fellow “hit” rappers, Common has also frequently partnered with a R&B singers, including D’Angelo, Pharrell, as well as John Legend himself—on the 2010 remake of the 1975 R&B song “Wake Up Everybody” (by Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes), inspired by Obama’s re-election in 2008.“

Analysis

“Glory” arose after Common was asked by director Ava DuVernay to produce a song to close the historic drama film Selma (2014), in which Common played the role of minister James Bevel. Not surprisingly, given their professional connections and mutual social penchants, Common immediately thought of Legend as an ideal collaborator, suggesting to him several song titles, including “Glory”. Although the song enjoyed only modest chart success (rising to No. 49 on Billboard’s Hot 100), it went on to win the 2015 Academy Award for Best Original Song. [6]

Given the theme of the film — the 1965 Civil Rights march from Selma to Montgomery led by Martin Luther King, Jr., John Lewis, and James Bevel—it is fitting that the underlying musical idiom of “Glory” is gospel, that most traditional genre of the African-American church. More specifically, it may be labeled as “neo-soul”, a tier 3 genre often aligned with Legend’s output. Soul, of course, is the 1950s and ‘60s genre developed by artists like Ray Charles, Etta James, Sam Cooke, and James Brown that secularized gospel music by incorporating elements of rhythm & blues and jazz. As Legend noted to Rolling Stone in 2015:

“I really thought about the music I grew up on, which was gospel music, and how important it was in the [civil rights] movement . . . So many of our great soul artists grew up in the church as I did, and I think understanding that connection between the spiritual and the secular and putting that to music is an important part of what we do." [7]

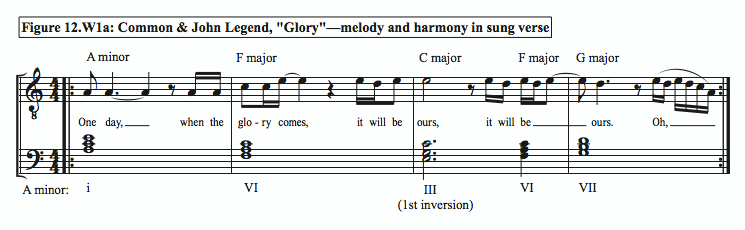

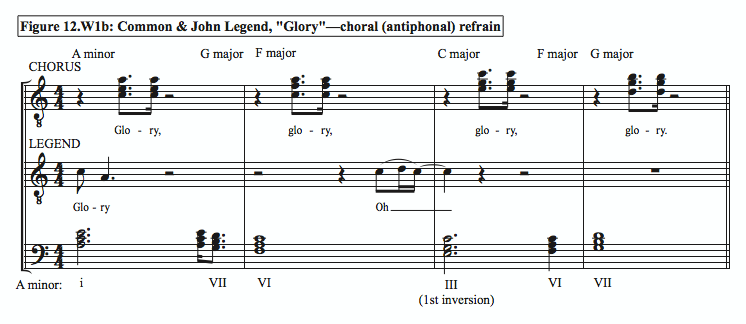

“Glory” begins straight away with Legend singing an 8-bar vocal verse, based on a twice-repeated 4-bar modal chord progression in A minor, accompanying a gospel-tinged melody. The lyric underscores the uplifting gospel-like message of the song as a whole: “One day when the glory comes, it will be ours.” This then leads into a short, 4-bar refrain (on the word “Glory”) using the same chord progression that to some degree antiphonally (call-response) alternates between a gospel choir and Legend’s often melismatic (ornate) vocalizing (Figure 12.W1a-b):

Common then enters with a 16-bar rap above the same chord progression, though now orchestrated with piano, rhythmic strings (at the 8th-note), and periodic percussion consisting of timpani and cymbals. In these 16 bars, the rapper delivers a sharp political commentary that provides context to Legend’s more generically hopeful message. Specifically, Common connects the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s with the more recent unrest in Ferguson, Missouri following the 2014 fatal shooting of Michael Brown, an 18-year-old African American male. In his first verse, Common moves from the Ferguson to Alabama, and back again:

One son died, his spirit is revisitin' us

Truant livin', livin' in us, resistance is us

That's why Rosa sat on the bus

That's why we walk through Ferguson with our hands up

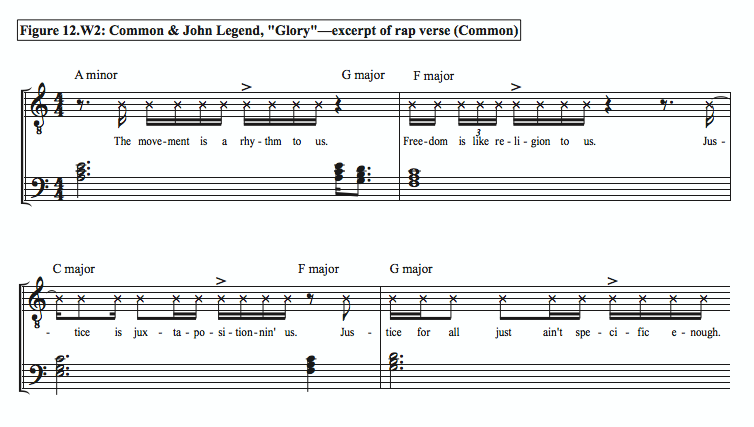

In his rap delivery, Common seems to straddle the approaches of Snoop Dogg and Eminem: mixing the former’s laid-back (behind-the-beat) style with the latter’s use of insistent rhythmic repetition (starting from “The movement is rhythm to us ”); although Common lacks Eminem’s often virtuosic level of syncopation, found, for example, in “Lose Yourself”, his use of internal repetition here provides an insistent and alluring groove—as seen in Figure 12.W2:

“Glory” continues with another vocal verse and choral refrain, now accompanied by strings and percussion as well. With all these distinct sections all set to the same 4-bar chord progression, the form so far resembles the Baroque-era chaconne (like Pachelbel’s Canon ) or various pop examples using a short, cyclic chord progression.

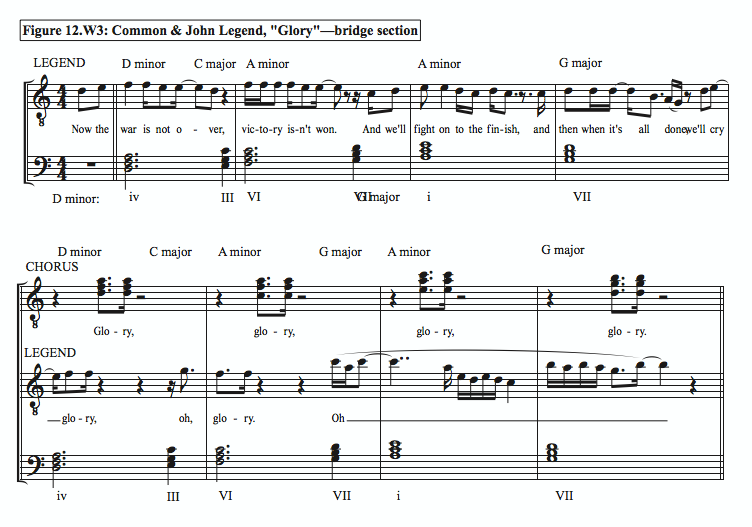

The pattern is broken, however, by a 4-bar bridge starting on D minor (the iv chord), which is extended into a varied antiphonal refrain (“Glory”), accompanied by strings, percussion, and brass (Figure 12.W3):

The original chord progression then returns to support a final rap verse: once again, the events of Selma are placed in relationship to external themes, specifically invoking both Martin Luther King and Jesus Christ—thereby reinforcing the song’s gospel foundations. Critically, Common implores the listener, in spite of the odds, to avoid violence: “The biggest weapon is to stay peaceful”—whereby he overtly counters the “disillusionment” in the Civil Rights activism noted above with regard to EWF’s “Shining Star”. And, indeed, delivering such a message of hopeful activism is a prime motivation for Common as a hip hop artists, as he told Rolling Stone magazine: “This is who I want to be… to speak up and say things that can impact people's lives, and things that can be inspiring to human beings."

The end of Common’s second verse elides with the return of a final sung verse, and extended refrain. The collective result of all this is a highly evocative discourse that creatively balances variety (sung vs. rap vocal delivery) and unity (repeating harmonic progressions), set in a rich orchestral pallet. In so doing, “Glory” supports well the emotional magnitude of the film’s subject matter, while likewise providing an uplifting way for Subject 4 to end a rich musical day.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] See Britt, Bruce. “John Legend is Living Up to His Name.” MusicWorld (website), March 3, 2005. For more on Legend’s career and output, see, for example, his biography on the All Music and Wikipedia websites.

[2] The song became the first ballad in 18 years to top the Billboard R&B chart; the song—written for his then-fiancé Chrissy Teigen—has since become a staple of weddings, and as Legend notes, helped take his career to superstardom. See McLean, Craig. “John Legend Interview: ‘All of Me’ has taken my fame to another level.” Independent , June 5, 2014.

[3] Ibid. Kanye’s most infamous outburst is undoubtedly: “George Bush doesn’t care about black people”—said on camera during NBC’s “A Concert for Hurricane [Katrina] Relief” on September 2, 2005. See Strachan, Maxwell. “The Definitive History of ‘George Bush Doesn’t Care About Black People’: The story about Kanye West’s most famous remarks”. Huffington Post , August 28, 2015.

[4] More on Common’s career can be found in his autobiography: Common. One Day It’ll All Make Sense . New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011; see also his biography on the All Music and Wikipedia websites.

[5] Cited in Martens, Todd. “Common has got it all going on.” Los Angeles Times , December 22, 2011.

[6] The song was also co-written with another social-minded rapper, Rhymefest (Che Smith).

[7] Newman, Jason. “’Glory’ Winds Best Original Song at Oscars, Brings Cast to Tears.” Rolling Stone Magazine , February 22, 2015.

- Page 434

( More on the East-West rivalry ):

The rivalry followed upon the commanding success in the late 1980s and early 1990s of West Coast rappers like N.W.A., and Dr. Dre, and the resurgence of East Coast rap by artists like Notorious B.I.G. and Jay-Z in the mid-1990s. Beginning as personal attacks by individual artists (e.g., Tim Dog’s “Fuck Compton”), the feud escalated into a label war between Sean Comb’s Bad Boy (New York) and Suge Knight’s Death Row (Los Angeles)—culminating in Knight’s signing of New York-based Tupac Shakur to Death Row. The rivalry turned deadly on several occasions, most famously in the shootings of Tupac in Las Vegas (September 1996) and Notorious B.I.G. (March 1997).

- Page 434

( More on the “bastardization” of rap via white-owned labels ):

To wit, many once small, black-owned labels are now owned by major labels: for example, Bad Boy is owned by Sony, Def Jam is owned by Universal, etc.

- Page 436

( More on Snoop Dogg’s legal run-ins ):

Most notorious of Snoop’s many run-ins with the law occurred in August 1993: while recording the album Doggystyle (the album with “Gin & Juice”), Snoop was arrested for the gang-related murder of Philip Woldemariam; he was, in fact, driving the car when Snoop’s bodyguard McKinley Lee shot and killed Woldemariam. Celebrity lawyer Johnnie Cochran defended Snoop and Lee, and both were acquitted—though Snoop’s legal challenges surrounding the case persisted for some time; for more, see the “Legal incidents” section of Snoop’s Wikipedia entry.

- Page 437

( More on the sampled content of “Gin & Juice” ):

Several sources, including Wikipedia, incorrectly state that “Gin & Juice” samples the bass part of “I Get Lifted”—only the drums are “lifted”.

- Page 440

( An example of the premature claims of hip hop’s decline ):

An example is when Time Magazine suggested that the music market (in 2007) “is telling rappers to please shut up. While music-industry sales have plummeted, no genre has fallen harder than rap.”

- Page 445

( More on the volatile relationship between Eminem and his wife Kim Mathers ):

The 30-year relationship between Eminem and Kim Scott Mathers is among the most public, if not sordid, in pop music history. The two met as teens, have one child (Hailey) together, and have been married and divorced twice. The drama between them includes tragedy (the suicide of Kim’s twin sister in 2016), two attempted suicides by Kim, and repeated struggles with drug abuse.

- Page 446

( More on Eminem’s history of attacks on celebrities ):

A seemingly comprehensive list of the celebrities of Eminem has attacked—as of late 2013—can be found in Richards, Jason. “Every Celebrity Eminem Has Ever Dissed.” The Atlantic , November 7, 2013.

- Page 447

( More on Eminem’s approach to and history of sampling ):

Eminem is certainly not averse to sampling or borrowing, but adopts the practice less commonly than many other hip hop artists. Further, the sources he does use are less from 1970s R&B than from classic rock artists like Led Zeppelin, Heart, and Aerosmith—as well as more obscure artists like Lesley Gore and jazz pianist Dave Grusin. In the case of his 2000 song “Kill You”, Eminem seemingly borrowed the beat used in French jazz pianist Jacques Loussier’s 1979 song “Pulsion”—though without permission; in April 2002, Loussier filed a $10 million lawsuit again Eminem and Dr. Dre; the caase was settled out of court in 2004. See, for example, Dansby, Andrew. “Composer Addresses Eminem Suit.” Rolling Stone Magazine , April 3, 2002.

- Page 449

( More on the source of That’s the Way of the World ):

This title was initially a film project—produced by Sig Shore, who also produced Super Fly , and starring EWF—about a struggling record company. EWF provided the soundtrack, but fearing the film would be a bomb (as it was), they released a stand-alone album with the same name prior to the film’s release.

Principal Bibliography:

Jeff Chang, Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2007)

Becky Blanchard, “The Social Significance of Rap and Hip-Hop Culture,” Journal of Poverty & Prejudice (Spring 1999)

Jeff Weiss and Evan McGarvey, 2pac vs. Biggie: An Illustrated History of Rap’s Greatest Battle (Minneapolis, MN: Voyageur, 2013)

Snoop Dogg with Davin Seay, Tha Doggfather: The Times, Trials, and Hardcore Truths of Snoop Dogg (New York: Harper Collins, 2000)

Josh Eells, “The Trials of Kendrick Lamar,” Rolling Stone , June 22, 2015

Jake Brown, Dr. Dre in the Studio: From Compton, Death Row, Snoop Dogg, Eminem, 50 Cent, The Game & Mad Money (New York: Colossus Books, 2006)

Chris Molanphy, “Introducing the King of Hip-Hop,” Rolling Stone , August 15, 2011

Maurice White and Herb Powell, My Life with Earth, Wind & Fire (New York: HarperCollins, 2016)

Newman, Jason. “’Glory’ Wins Best Original Song at Oscars, Brings Cast to Tears.” Rolling Stone Magazine , February 22, 2015

External Links:

"Hip-Hop" (Encylopaedia Britannica)

Kendrick Lamar Official Website

Earth, Wind & Fire Official Website