Summary:

Chapter 6 unwinds the fourth of the five principal musical parameters: form, which is given the anthropomorphic simile of the “shape of music”—highlighting the importance, as well articulated by Oscar Wilde, of form in defining the essence of an artwork. The chapter begins with a high-level look at the formal concepts of unity and heterogeneity before unwinding the basics of form: sections, phrases (including antecedent / consequent pairings), and the standard analysis techniques of defining formal sections and phrases. It then highlights three primary formal functions: repetition, contrast, and variation—culminating with an in-depth formal analysis of Beethoven’s “Für Elise”. The chapter then concludes by providing an historically-based discussion of six common formal templates (strophic, binary, ternary, rondo, variations, and through-composed) and four formal types (blues, the 32-bar jazz standard, the sectional pop / rock song, and sonata).

Supplements:

- Page 187

( Completed analysis of Beethoven’s “Für Elise”):

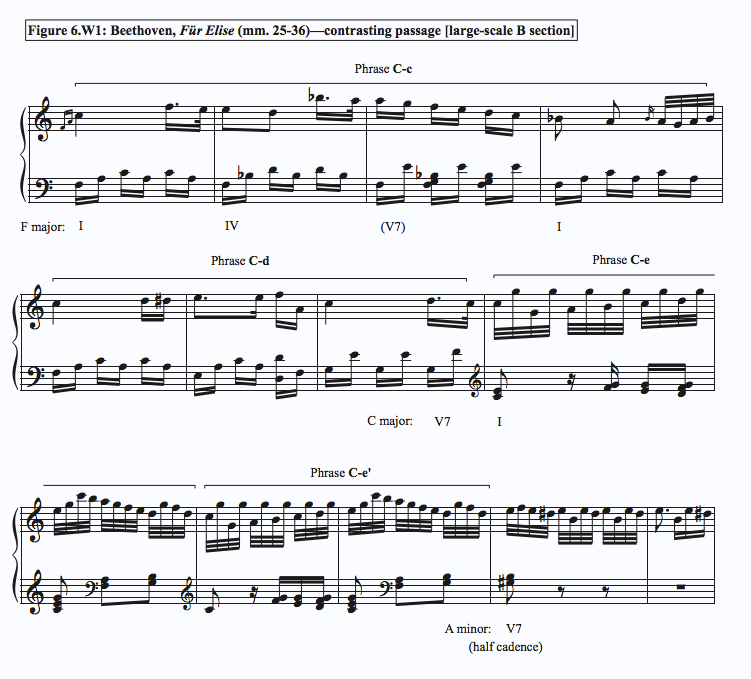

The following is the remainder of the formal analysis of Beethoven’s “Für Elise”, from measure 25 (see the main text for the analysis of measures 1-24)

Following this section, however, Beethoven introduces us to a section with considerably more contrast than the B section we identified earlier (Figure 6.W1):

Here the contrast of musical material is considerably more palpable: a new key (F Major), a different accompaniment pattern, etc. We would seemingly call this section C. This section initially consists of two phrases, that although they both start on the same note (C), are decidedly different, whereby we can label them as C-c—C-d. Upon reaching a cadence in measure 32 (to C Major), Beethoven immediately launches into yet new material, much faster (32nd notes) and more rhythmic; the four measures are actually two nearly identical 2-measure phrases (C-e—C-e´), which lead us once again to a half cadence in A minor (measure 36).

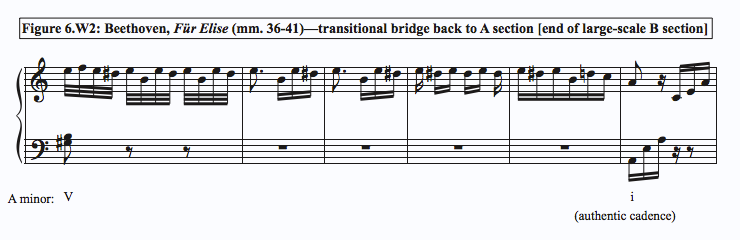

The following 5 measures (measures 36-40) maintain the same harmony (E), and are what may be cal led “transitional material”, not really a part of any one section, not really a phrase at all, but acting as a kind of bridge between sections.

The transition leads us, as we anticipate by its rather teasing nature, back to the “main theme” in measure 41:

Beethoven here repeats exactly the entire sequence found from measure 1-24, thought without the repeats. As such we might quickly assume assigning this passage with the same diagram as before: A-a—A-a´—B-b—A-a—A-a´. But at this point we might also wonder if by bringing back the entire passage, Beethoven is considering these 24 measures as one big section—A. In such a format, the labeling would be A-a—A-a´—A-b—A-a—A-a´; this would also mean that the section starting at measure 24 is not C, but rather B; and thus the larger pattern created thus far would be A-B-A. For the sake of argument, we’ll here adopt this revised perspective.

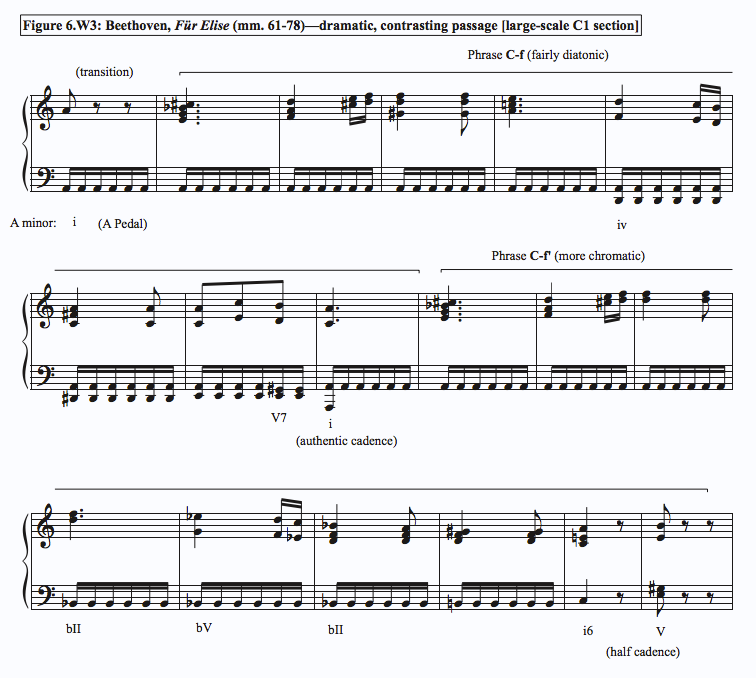

Coinciding with the cadence at the downbeat of measure 61, Beethoven then launches into yet another contrasting section (Figure 6.W3):

Following 1 measure of transition, the right hand ( treble clef ) of the piano plays a more sustained, chordal melody as the left hand ( bass clef ) of the piano repeats the same pitch in steady 16th notes, creating a level of tension and rising drama. Specifically, we hear 2 phrases (measures 62-69, 70-78) that begin similarly; but whereas the first stays diatonic and concludes with an authentic cadence (measure 69), the second is more chromatic (via ascending motion in the left hand), ending this time with a half cadence (measure 78). Using our revised scheme, these phrases would be labeled as C-f—C-f´.

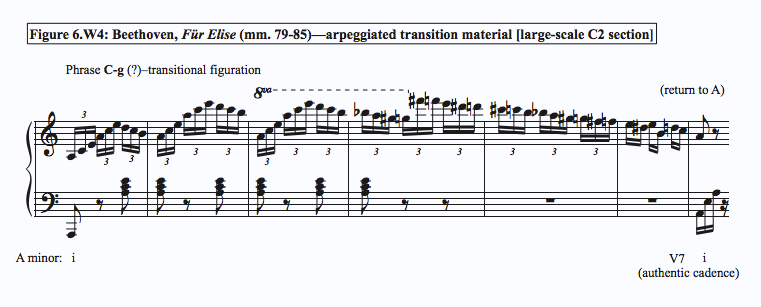

The music then continues with another contrasting burst of energy (Figure 6.W4):

The passage here begins as a series of fast (16th note triplets) rising arpeggios (broken chords) in the right hand supported by rhythmic punctuation in the left hand. Harmonically, we stay in A minor for the first 3 bars before the right hand begins a chromatic descent (by steady half-steps) leading to the pitch (e) that will next re-introduce the “main theme”. Despite the contrast between the ascending arpeggios and the descending chromatic line, this passage likely strikes the ear as a single phrase, by virtue of its lack of articulated separation. But is this a 3rd phrase within the larger section (C-g), or a separate section in and of itself (D-g)? Given its short length, and the fact that it is largely acting as a “transitional” phrase leading back to the A section, the former seems most logical.

The return to the A section, moreover, is but a straightforward repetition of the A section as heard in measures 41-60 and measures 1-24 (see Chapter 6, Figures 6.15 and 6.16):

This exact repetition of A (A-a—A-a´—A-b—A-a—A-a´) reinforces our earlier hunch that the passage should be conceived of as a single “large-scale” section, which acts as a symmetrical “anchor” for the work as a whole. Thus, as noted in the main body, the full, high-level plan for “Für Elise” is thus A-B-A-C-A, the classic structure of a rondo. In all, there is a balance of repetition (the recurring A section, with its own internal repetition) and contrast (the B and C sections, including internal contrast within C)—as follows:

A = measures 1–24

B = measures 25–40

A = measures 41–61

C = measures 62–84

A = measures 85–end

This formal dynamic gives the overall work its natural, “organic” quality, and provides the listener with both anticipated familiarity and dramatic surprise. This is further embodied in the A section itself, which holds its own symmetrical structure of A-B-A. Indeed, both interpretations are correct at once—one at the micro-level, the other at the macro-level.

Form, in short, is a rich, and wondrous thing, especially in the hands of a master like Beethoven.

- Page 193

( More on the structure of ternary form ):

Quite frequently, ternary form provides an overall framework within which are contained 2 distinct binary forms—as in the Da capo aria of 17th and 18th century opera or the Minuet-and-Trio of the 18th century instrumental music. These would be diagrammed as AAA´A´—BBB´B´—AAA´A´ (or simply AA´ on the return). This configuration is referred to as compound or composite ternary, as opposed to simple ternary, which is ABA. In either event, the B section is often notably contrasting to the A section in style and character (e.g., a rhythmic B section compared to a more lyrical A section, or vice versa).

- Page 197

( Another formal interpretation of “Happiness is a Warm Gun” ):

A slightly different formal schema for the song is described in Osborn, Brad. “Understanding Through-Composition in Post-Rock, Math-Metal, and other Post-Millennial Rock Genres.” Music Theory Online 17, no. 3 (2011): (3). For example, Osborn identifies the 3/4 section (“When I hold you…”) as E’, that is a mere variant of the previous section (“Happiness is a warm gun”); he does so given the use of the same chord progression—despite the striking differences in meter, melody, and feel.

- Page 200

( Specific harmonic progressions of blues songs discussed in main text ):

The 8-bar progression for “Heartbreak Hotel” is: I7 (4 bars)–V7 (2 bars)–V7–I7; the 16-bar progression of “I’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man” is: I7 (8 bars)–IV7 (2 bars)–I7 (2 bars)–V7–IV7–I7 (2 bars); the 24-bar progression of “Slow Down” is: I7 (8 bars)–IV7 (4 bars)–I7 (4 bars)–V7 (2 bars)–IV7 (2 bars)–I7 (4 bars); as you may note, this is simply doubling the length of the standard 12-bar blues.

- Page 201

( More on dominantization of the tonic ):

The expression “dominantization of the tonic”, moreover, has been cited as a rare phenomenon in the Western classical repertoire in the 19 th century, such as in the fugue of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata in Ab, Op.110 . See Ormesher, Richard. Beethoven's instrumental fugal style: an investigation of tonal and thematic characteristics in the late-period fugues. Ph.D. thesis, University of Sheffield, 1989: 55.

- Page 202

( More on the varied use of “chorus” and “refrain” ):

The overlap of these two terms—chorus and refrain—originated in the sheet music of “parlor” or “plantation” songs in the 19 th century, such as those by Stephen Foster. The formal term “refrain” was increasingly labeled “chorus” in the sheet music to signify this as the repeated section to be sung by the whole group (the chorus, or troupe in a minstrel show), as opposed to the changing verse, sung by a soloist. While a refrain was initially associated with a single line or phrase, it gradually came to signify the entire principal section—as in the full 32-bar AABA form. The term “chorus” began to supplant “refrain” in the jazz era, namely to indicate an improvised solo iteration of the full song (refrain) form, and was maintained in the pop / rock era for the repeated (refrain) section. See, for example, Von Appen, Ralf, and Markus Frei-Hauenschild. "AABA, Refrain, Chorus, Bridge, Prechorus—Song Forms and their Historical Development." Samples. Online-Publikationen der Gesellschaft für Popularmusikforschung (2015).

- Page 202

( More on the initial implications of the AABA, etc. song form ):

Interestingly, the AABA form, going back to Irving Berlin’s “Everybody’s Step” (1921) was initially considered more “jazzy” (that is, African American) than other versions of the 32-bar form—perhaps due to the repeating AA, which recalled the call-response opening of the blues.

- Page 204

( More on the role of the verse in an AABA song form ):

Put into the context of the formal templates discussed above, the verse-refrain arrangement is a variety of the binary form (ABB, etc.), with the A section of considerably lesser importance. When dispensed with, the pure refrain form (AAA, etc.) is clearly strophic. The inclusion of the verse, again, is relatively rare in recordings and performances of standards. Its use is primarily limited to vocal renditions, where the lyrics provide preparation to the sentiments of the refrain.

- Page 204

( Details on Miles Davis’ rendering of the “Just Squeeze Me” AABA form ):

Miles’ recording differs from other, more “generic” roadmaps of jazz standards only in that the return of the “head” after the last solo includes only the second half of the song; more common is that the entire “head” would be repeated.

- Page 208

( More on distinction of AABA and verse-chorus song formats ):

When verse-chorus songs have a bridge—namely, one that appears outside its “normal” position within an AABA format—the distinction between the two becomes more theoretical than experiential. That is, the listener is simply conscious of a progression from verse to chorus to bridge in some distinct and artistic way, as a flow of sections.

- Page 211

( More on the Baroque dance suite ):

During the baroque era, a key distinction was between the “sonata da camera” (chamber sonata)—in essence a prelude followed by a set of dance movements; and the less common “sonata da chiesa” (church sonata)—a 4-movement instrumental work, alternating slow and fast. See Mangsen, Sandra. “Sonata da camera” and “Sonata da chiesa.” Grove Music Online (2001).

- Page 213

( More on common changes in Exposition material during the Recapitulation ):

Not infrequently, such changes will accommodate the changed register (pitch placement on the instruments) otherwise necessitated by the lack of a modulation.

- Page 216

( More on Sonata form’s unique mix of binary and ternary elements ):

As Webster continues, the argument that sonata form is either binary or ternary are “idle and superficial.” Further, some theorists have seen a kinship with the “rounded binary” (A—BA), and yet it must be recalled that the second “A” there involves an exact repetition of the first—whereas in sonata form, a fundamental fact is that the secondary theme returns now in the tonic. Indeed, concerning sonata as a template or a type, one could also say that it is a formal type that combines two (or more) formal templates.

Principal Bibliography:

Arnold Whittall, “Form,” Grove Music Online.

Elaine Sisman, “Variations,” Grove Music Online.

Albert Murray and Paul Devlin’s, Stomping the Blues (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1976)

Ted Gioia, e History of Jazz (Oxford University Press, 2011)

Ralf von Appen and Markus Frei-Hauenschild, “AABA, Refrain, Chorus, Bridge, Prechorus—Song Forms and eir Historical Development,” Samples: Online- Publikationen der Gesellschaft für Popularmusikforschung (2015)

Charlie Gillett, e Sound of the City: e Rise of Rock and Roll (New York: Outerbridge & Dienstfrey, 1970)

John Covach, “Form in Rock Music,” in Engaging Music: Essays in Music Analysis , ed. Deborah Stein (Oxford University Press: 2005)

Charles Rosen, Sonata Forms (New York: W. W. Norton, 1988)

James Webster, “Sonata Form,” Grove Music Online

External Links:

"Musical Form" (Encyclopaedia Britannica)