Summary:

Chapter 11 is the third of seven chapters dedicated to one of the key “genotypes” presented in this book: that dedicated to jazz. The chapter begins with an aesthetic and sociological review of jazz, along with an offering of ten reasonable touchstones for this species. It then proceeds to the main thrust of the chapter: the unwinding of the historical and then musicological details behind the five “hits” for Subject 3, a devotee of the jazz species. These five (four in the book, one on the website only) are: Dizzy Gillespie’s “Be-bop”; Wayne Shorter’s “Footprints”; Bela Fleck’s “Railroad”; Antônio Carlos Jobim’s “Águas de Março”; and Bill Evans’ “Peace Piece”. The chapter closes with a range of potential candidates for addition / future hits for Subject 3, based on proximity on various levels to the five seeds.

Supplements:

- Page 377

( Presentation of 5th “hit” discussed for Subject 3: Bela Fleck and Abigail Washburn’s “Railroad” ):

The following is the full discussion of the 5th song of the jazz genotype, Bela Fleck and Abigail Washburn’s “Railroad”—heard on the drive home from work. It was excluded from the main text and delimited to the website only:

The Drive Home: Fleck and Washburn’s “Railroad”

Béla Fleck and Abigail Washburn’s “Railroad” is, after the last 2 selections, a decided change of pace for Subject 3. On many levels it cannot even be called jazz, but rather “progressive bluegrass”, or something similar. And yet, the recording does embrace key elements of the jazz aesthetic: virtuosic improvisation, chromatic re-harmonization, etc. It also introduces an element not heard thus far: the voice. As with Subject 2, therefore, a proper sense of Subject 3’s taste genotype seems to require more than just 2 songs: “Railroad”, that is, is far from “mainstream” jazz.

Background

Béla Fleck holds the rare distinction of being a decidedly “hip” banjo player. As much as anyone he has helped transform the public image of the instrument from a subject of derision (think Hee Haw ) to one of enthusiasm and wonder—at least to those paying attention. In 2013, the New York Times called Fleck “the most popular living banjoist, having done much to push the instrument beyond bluegrass terra firma into jazz, classical music and beyond.”[1] He was born in New York City in 1958, and seemed to have been destined for a life in music: his absentee, classical-crazed father christened him Béla Anton Leoš—the first names of composers Bartók, Dvořák, and Janáček, respectively; his brother was named Ludwig! And yet, not unlike Gillespie and Shorter, Fleck didn’t truly heed the call until his teens, when he first heard banjoist Earl Scruggs play the theme of the Beverly Hillbillies, and then “Dueling Banjos” from the film Deliverance. He was hooked, and got his own banjo at age 15—studying privately with master banjoist / teacher Tony Trischka.

Fleck’s earliest professional endeavors took place within the confines of bluegrass—with the mandolin and fiddle-based groups Tasty Licks and Spectrum.[2] Yet, from an early age he also absorbed a much wider array of influences: Charlie Parker, progressive rock band Yes, Bach, etc. After tepid steps into the “progressive bluegrass” realm, Fleck formed the influential jazz-bluegrass fusion group Béla Fleck and the Flecktones, in 1988.[3] On albums like Flight of the Cosmic Hippo (1991), the Flecktones introduced bluegrass to a new audience, gaining both popular and critical success, including 5 Grammy Awards. The jazz magazine Downbeat , for example, likened the Flecktones’ virtuosic, ambitious, and eclectic sound to Wayne Shorter’s influential fusion band Weather Report .[4]

But even beyond this genre-busting ensemble, Fleck has indulged in a striking diversity of solo and collaborative projects. His collaborators hail from almost every musical realm: Earl Scruggs and bassist / composer Edgar Meyer (bluegrass); violinist Joshua Bell and guitarist John Williams (classical); pianist Chick Corea and saxophonist Branford Marsalis (jazz); Dave Matthews Band and Phish (rock); and Malian ngoni (African banjo) player Cheick Diabate and the Tuvan vocal group Alash (world), to name but a few. The resulting recordings and tours have again yielded critical acclaim (including several Grammys), and a devoted fan base. Among recent collaborations too are those with his singer and banjoist wife Abigail Washburn, both as a duo and in their bluegrass-world fusion group Sparrow Quartet. Clearly Fleck relishes in taking his fellow musicians and his fans—like Subject 3—on a wild ride, dazzling in technical prowess and defying in expectations of style and genre.

Analysis

“Railroad” is a fresh take on a classic American folksong, “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad”—first published in 1895.[5] The track appears on Fleck and Washburn’s 2014 self-titled album, and features Washburn on vocals, with both playing banjo.

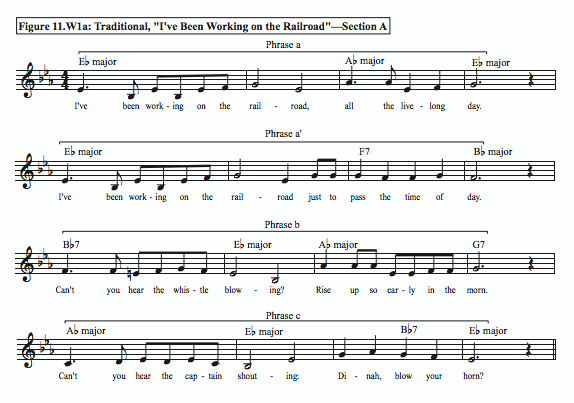

Most striking from an experiential standpoint takes place in the realm of harmony: a shift in mode from the original folksong—from major to minor. It is fairly common in creating a new arrangement of a familiar song to change the meter, for example from duple to triple—as the Flecktones do, for example, on their inventive 1991 version of the Beatles’ “Michelle”; more rare, however, is to change the mode. Indeed, their version does more than just shift the tonic from major to minor, it wholesale alters both the harmony and melody of the original—though maintains the original melodic rhythm. Here are the opening four melodic phrases of both the original and the Fleck-Washburn version (Figure 11.W1a-b):

Specifically, the first 1:35 of the 3:36 tune remains largely on the tonic (C minor), moving only to the dominant (G7) just prior to the end of each main section. The harmonic language of “Railroad”, however, is not as simple as the above implies, as Fleck’s obbligato banjo continually adds chromatic and polychordal inflections above the C minor pedal outlined by Washburn’s arpeggiated triad and diatonic melody. How’s that for a technical-laden sentence—see how far you’ve come?

The result of this adaptation is a driving sonority akin to classic minor bluegrass songs like “Shady Grove” or Bill Monroe’s fiddle tune “Jerusalem Ridge”. Up to this point, the musical form has been: Intro—A1 (“I’ve been working on the railroad”)—A2 (“Can’t you hear the whistle blowing”)—B (“Dina won’t you blow”)—Interlude—A3 (“Someone’s in the kitchen with Dinah”)—C (“Singin' fee, fie, fiddly-i-o”).

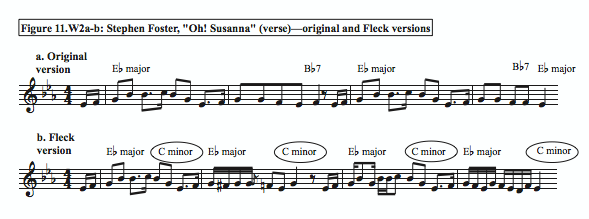

Then, however, “Railroad” introduces a quodlibet (melodic medley) quality with an adaptation of Stephen Foster’s “Oh! Susanna” on the banjo. This too is subjected to minor mode treatment: resolving each phrase from Eb major to C minor, instead of the original dominant, then tonic (Figure 11.W2a-b):

The neo-“Oh! Susanna” refrain is repeated and further expanded into a solo section by Fleck. The passage aptly demonstrates his technical prowess on the banjo, with jazz-inflected strings of 16th notes and blues-based ostinatos. Washburn’s vocals then return to the A3 section, continuing onto the C section, which is repeated much like a chorus—as before, with Fleck adding vocal harmony. This is followed again by Fleck playing a dazzling solo upon the adapted “Oh! Susanna”. The recording concludes with a return to the A section, this time with new, original lyrics.

Indeed, Washburn’s vocal delivery is also a major part of the listening experience: her breathy, twangy, and well-articulated timbre nicely complimenting the “old time” style of the recording. In sum, “Railroad” may not possess the virtuosic pizazz of “Be-bop” or the musicological sophistication of “Footprints”, but the recording’s complex form, harmonic coloring, and Fleck’s impressive banjo “chops”—alongside its moody, down-home feel—provide much to engage Subject 3’s musical taste.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Finane, Ben. “A Gathering of Banjo Master.” The New York Times , January 11, 2013. For more on Fleck, see his biography at All Music, Wikipedia, etc.

[2] For a general intro to Bluegrass music, see, for example, Rosenberg, Neil V. Bluegrass: a history . Vol. 433. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2005.

[3] The other original members of the group were acclaimed bassist Victor Wooten, his brother Roy Wooten on MIDI drums, and Howard Levy on harmonica and keys.

[4] Koransky, Jason. “Béla Fleck and the Flecktones: Expanding Worlds” (interview). Downbeat , October 2003.

[5] The song was originally titled “Levee Song”, constituting the first section only; the modern version known today is in fact a compilation of 3 songs: the 2nd part (“Someone in the kitchen with Dinah”) is from the song “Old Joe” (1830s); the 3rd section “Dinah won’t you blow” is a more modern addition (1940s), according to Peter Seeger added by college students. See Ruehl, Kim. “Working on the Railroad: Railroad Labor Song or Princeton Stage Review?” ThoughtCo. (website), October 26, 2017.

- Page 382

( More on Dizzy’s stints with various big bands ):

Dizzy also played one short stint with Duke Ellington’s band, in New York in fall 1943, an experience the trumpeter found less than fulfilling.

- Page 382

( More on Dizzy’s stints with various big bands ):

Dizzy also played one short stint with Duke Ellington’s band, in New York in fall 1943,

- Page 382

( Supplement to footnote, on origins of “be-bop” and its reminiscences ):

As such, the origins of the term “be-bop” is not dissimilar to the origins of the term “hip hop”, initially just the opening nonsense word of “Rapper’s Delight” (1979)—which fans then requested with “Hey, play that ‘hip hop’ song…”

- Page 387

( More detail on the A7 alt chord used in “Footprints” ):

Specifically, the alternation is: b9, #9, #11, and b13. The chord changes in this passage have been the subject of much discussion and debate in wonky jazz circles; see for example: Spitzer, Peter. “Those ‘Footprints’ Changes. Peter Spitzer Music Blog , July 4, 2012.

- Page 388

( More detail on the identity of 6/4 meter ):

That is: 6/4 is in general an odd meter— unless the principal “beat” is felt at the level of dotted half-note, in which case the count would indeed be 1-2-3/4-5-6, but where the beat is a quarter note; in this scenario, the meter can be considered compound duple, with the primary sub-division at the level of quarter note, as opposed to the more typical compound duple meter—6/8 meter, where the eighth note is that principal subdivision. Underscoring the complexity is the fact that a principal written source of the song, the Real Book (jazz fake book) presents the song in 3/4 meter.

- Page 389

( More on Herbie Hancock’s solo on “Footprints” ):

This is in contrast to the largely melodic—and quite virtuosic—solo taken by Hancock on his recording of the song with Shorter’s quartet.

- Page 391

( More on fame of “Águas de Março”):

As an example of its acclaim, the song was rated the “all-time best Brazilian song” in a poll of more than 200 Brazilian journalists, musicians and other artists conducted by Brazil's leading daily newspaper, Folha de S. Paulo . See Nascimento, Elma Lia . "Calling the Tune. ” Brazzil , September 2001.

- Page 394

( The author’s reflection on Bill Evans’ introduction to music ):

Not unlike the author’s own story (as discussed in Interlude C), Bill’s brother Harry started first, whereupon Bill began to play his songs by ear. See Pettinger. Bill Evans : 9.

Principal Bibliography:

Ted Gioia, The History of Jazz (Oxford University Press, 2011)

Gary Giddins Visions of Jazz: The First Century (Oxford University Press, 1998)

Alyn Shipton, Groovin’ High: The Life of Dizzy Gillespie (Oxford University Press, 2001)

Michelle Mercer, Footprints: The Life and Work of Wayne Shorter (New York: Penguin, 2007)

Helena Jobim, Antonio Carlos Jobim: An Illuminated Man (Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard Corporation, 2011)

Peter Pettinger, Bill Evans: How My Heart Sings (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998)

External Links:

"Jazz" (Encylopaedia Britannica)

Antonio Carlos Jobim (Encylopaedia Britannica)