Chapter 13 is the fifth of seven chapters dedicated to one of the key “genotypes” presented in this book: that dedicated to electronica or EDM (electronic dance music). The chapter begins with an aesthetic and sociological review of electronica, along with an offering of ten reasonable touchstones for this species. It then proceeds to the main thrust of the chapter: the unwinding of the historical and then musicological details behind the five “hits” for Subject 5, a devotee of the EDM species. These five (four in the book, one on the website only) are: the Chemical Brothers’ “Hey Boy Hey Girl”; Armin van Buuren’s “Embrace”; Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians , Messinian’s “Holy Ghost”; and Brian Eno’s “Always Returning”. The chapter closes with a range of potential candidates for addition / future hits for Subject 5, based on proximity on various levels to the five seeds.

Supplements:

- Page 455

( Presentation of 5th “hit” discussed for Subject 5: Messinian’s “Holy Ghost” ):

The following is the full discussion of the 5th song of the EDM genotype, Messinian’s “Holy Ghost”—heard as a winding down before bedtime. It was excluded from the main text and delimited to the website only:

On the Dance Floor: Messinian’s “Holy Ghost”

Messinian’s, “Holy Ghost” takes Subject 5 from the meditative and artful realm of serious minimalism to the high energy and fun of the EDM dance floor. In contrast to the lauded stature of Music for 18 Musicians , “Hoy Ghost” is a fairly obscure contemporary EDM track—showing that Subject 5 is not above looking far and wide, and in every electronica nook and cranny, to find the right “hits”.

Background

Messinian—literally, a geological era from around 6 million years ago—is the stage name of James Dean Fiorella, born in Los Angeles in 1979. In his own words he experienced an upbringing peppered by “the adversity of poverty, homelessness, drug addiction, and daily fistfights.”[1] Music was key to overcoming these challenges, especially hip hop (Public Enemy, N.W.A., etc.); he began writing his own rap lyrics at age 11. At the same time, he was early exposed to rock and R&B—from Jimi Hendrix and the Doors to James Brown and Otis Redding—largely through his mother who played piano. In his teens, Fiorella moved to Philadelphia, where he discovered the budding electronica scene there, and began to construct his own beats; he started working as a local DJ, taking the name Messinian.

While not a household name, Messinian is an active DJ and EDM producer— specifically aligned with the dubstep and drum and bass sub-genres. His live DJ shows at festivals and clubs around the world— from South Korea to Australia to Estonia and beyond—are known for their “wild” raw energy. As such, Messinian epitomizes the insider heart of the EDM culture and lifestyle, exclaiming in his bio that his life “is all about controlling microphones and turntables in front of wild crowds and taking the energy to a higher level.” His original mixes, most of which involve collaboration with singers and other DJs, have gained modest success—including several reaching the Top 20 in EDM-specific charts like Beatport. Most prominent of these hits, perhaps, is “Holy Ghost”.

Dubstep arose in South London in the mid-1990s, an offshoot of the slightly older drum and bass (D&B) sub-genre. As with related styles—breakcore, techstep, drumstep, brostep, etc.—these styles owe a debt to the Jamaican “sound system” genres popular in London in the late 1980s, such as dancehall, and ragamuffin. Each of these EDM styles eschews the steady 4-on-the-floor kick continuity of house or trance in favor of an actively syncopated drum pattern with loud snare hits on beat 3. Key to dubstep and D&B as well is a powerful and generally distorted bass line, overlaid with low frequencies (so-called “sub-bass”) that are more felt than heard. Dubstep is generally set at around 140 BPM, considerably slower than the 150-180 BPM range of D&B. The former also commonly incorporates a vocal “hook” (as is the case in “Holy Ghost”). Through the success of artists like Skrillex and Messinian, dubstep has begun to amass a huge international following in recent years.

Analysis

“Holy Ghost” is a dubstep track from 2011, featuring collaboration between Messinian and two other underground EDM artists: Helicopter Showdown (a collective of 4 “dubsteppers”) and Sluggo, a dubstep producer at the forefront of the fast rising mix between EDM and metal. This latter, incidentally, is not your grandfather’s heavy metal (ACDC, Black Sabbath, Iron Maiden, etc.), but the more recent and highly aggressive sub-genres of thrash metal, speed metal, death metal, etc.—featuring ultra-rapid tempos and screaming, indecipherable vocals. “Holy Ghost” limits its metal influence, however, to the raw intensity heard in the track’s two internal “bass drop” sections. As suggested, the track has enjoyed a degree of success, including multiple slots on the TV dance contest, So You Think You Can Dance —performed by “animator” and Season 9 runner up, Cyrus Spencer (2012).

In contrast to van Buuren’s “Escape”, “Holy Ghost” follows a good number of stylistic conventions for its style (dubstep) and in general observes a fairly straightforward musical discourse. The form follows a standard and symmetrical pattern of Intro—Vocal Chorus—Bass Drop 1—Vocal Chorus—Bass Drop 2—Outro. This displays not so much a lack of originality, but rather an embrace of a predictable timing / metric structure both for the listener and for DJs, who might mix-and-match this track with another—for example at the start of a “bass drop”.

Like the more generic “drop” of house and trance, the “bass drop” refers to a moment of arrival in the track, when a full texture / sound is presented following a more transparent or atmospheric section preceding it (often set up with a drum-roll “build”). These are the moments when EDM fans “go wild”. But whereas the “drop” in house generally brings in all sounds and instruments, the “bass drop” is limited to the drums and bass sonorities. These latter, however, are not simply a bass line, but instead a complex and varied bass “sound field”—including sub-bass frequencies, distorted samples, low- and mid-frequency oscillators, and any number of harsh industrial noises. “Holy Ghost” embraces such a distorted “sound field” in both of its “bass drops”—with a creative variety of sonorities that likely stand much behind the song’s success.

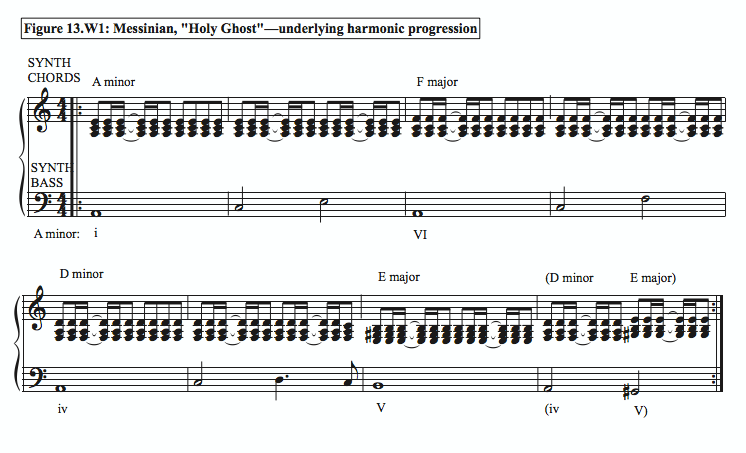

Supporting the above discourse is a simple, diatonic 8-measure chord progression in A minor, descending by 3rds: A minor—F major—Dmin7—E7. The progression—generally articulated via rhythmically pulsating chords and a sustained melodic bass line—is repeated twice to define each formal section noted above, with occasional variation, e.g., during the “bass drops.” Minor keys, indeed, are a typical musicological element of dubstep tracks (Figure 13.W1):

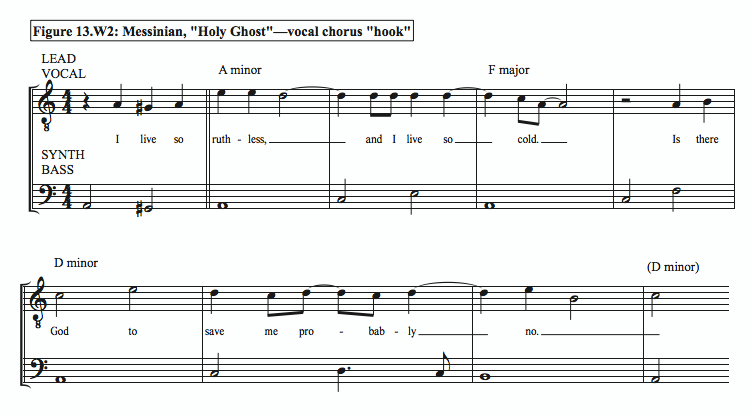

Beyond the bass “field” and syncopated drums, the instrumental sonority is comprised of 2 primary synth parts: a lively chordal rhythmic pattern and an ornate melodic obbligato. On top of these, then, are Messinian’s vocals—themselves subject to electronic manipulation. Following an instrumental 16-bar (pre-Intro) opening pass and another 16-bar pass with a distinct vocal obbligato, the vocal chorus hook is presented, supported by the sustained bass but without drums (Figure 13.W2):

As noted, this leads into the first “bass drop”—accompanied by occasional vocal insertions and short melodic riffs. The two main sections then alternate again, after which a bookend outro—with a highly altered variation of the chorus melody—closes the work. “Holy Ghost” may lack the compositional innovation or sophistication of Subject 5’s previous “hits”, but given its catchy vocal hook and especially high-energy, sonically rich “bass drops”, it clearly offers some essential electronica delights—and especially for a night on the dance floor with friends.

[1] Among the few places to learn more about Messinian include his biography on the Last.fm website.

- Page 461

( More on the drum groove of “Tomorrow Never Knows” and the Brothers ):

The groove of “Tomorrow Never Knows” in fact was used by the Brothers to close their live show, and in fact is referenced in a few songs, such as “Setting Sun” (1996) and more recently “I’ll See You There” (2015). With regard to the former, the surviving three members of the Beatles even believed the Brothers had sampled the drum part—which they were able to prove mistaken. See Fricke, David. “Hot Sounds: Chemical Brothers.” Rolling Stone Magazine , August 21, 1997.

- Page 465

( More on Jean-Michel Jarre and EDM ):

For more on Jean-Michel Jarre (son of French film composer Maurice Jarre), see his biography on the All Music and Wikipedia websites. Incidentally, in the late 1960s, Jarre studied with Pierre Schaefer, a pioneer of the electronic music technique known as “musique concrète"—dedicated to the experimental manipulation of previously recorded material, akin to what happens later in EDM music. See, for example, Wolfenberger, Abigail. “’Musique Concrete’ Is the Old-School EDM.” The Odyssey (website), February 13, 2017.

- Page 469

( More on Reich’s African experience and influence ):

As he stated in the Guardian interview (n. 548) upon his return from a trip to Nigeria: "It was like getting a pat on the back saying, yes, people have been writing repeating patterns for hundreds, maybe thousands of years, percussion is more interesting and magnetic to the ear than electronically generated sound, go home and continue. It was very encouraging because people were looking at me like I was crazy because I wasn't writing 12-tone serial music." He also supplemented his experience by studying books such as Jones, Arthur Morris. Studies in African music . Vol. 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1959—on Ghanaian drumming.

- Page 470

( More on David Bowie’s interest in Music for 18 Musicians ):

Bowie, for example, attended the European premiere of 18 Musicians in Berlin in 1976, and subsequently utilized the work’s pulsating mallets on the song “Weeping Wall”, released on Bowie’s album Low the following year. In 2003, he included Reich’s recording in his top 25 albums of all time; see Bowie. “Confessions of a Vinyl Junkie by David Bowie. Vanity Fair , November 20, 2003.

- Page 470

( Reference on the sampling of Reich’s music ):

For a listing of sampling of Reich’s music by EDM composers, see the results on www.whosampled.com.

- Page 470

( More on Reich’s take on the Beatles ):

In this Guardian interview, for example, Reich notes that despite living in San Francisco during the psychedelic era, and being friends with Phil Lesh of the Grateful Dead (the two were classmates at Mills College), rock music played no real role in his musical development. As he stated: “[Lesh] told me I had to hear Revolver by the Beatles. So I listened to it and I like it but I couldn't name you a tune that's on it. Sgt. Pepper came out, and I heard ‘A Day in the Life’ and I thought, wow, these guys are really remarkable, but it didn't have any influence on me.”

- Page 475

( More on Brian Eno’s take on Steve Reich ):

Eno indeed is critical of Reich—such as his recording of Drumming (1967), which, he says, “uses orchestral drums stiffly played and badly recorded. He’s learnt nothing from the history of recorded music.” By contrast, Eno “wanted to bring the two sides [classical and pop] together. I liked the processes and systems in the experimental world and the attitude to effect that there was in the pop, I wanted the ideas to be seductive but also the results.”

- Page 475

( More on Robert Fripp and the technique of “frippertronics” ):

Specifically, this involves the technique known as “frippertronics”—first used on the ( No Pussyfooting ) album. It has roots in the experimental tape looping techniques used in the early 1960s by classical composers like Pauline Oliveros and Terry Riley. See the interview of Robert Fripp by Andre LaFosse found on the “Looper’s Delight” website.

Principal Bibliography:

Daniel Warner, Live Wires: A History of Electronic Music 4th ed. (London: Reaktion Books Limited, 2017

Nick Collins and Julio d’Escriván, eds., The Cambridge Companion to Electronic Music (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017)

Jesse Saunders, House Music (Baltimore: PublishAmerica, 2007)

Alastair Fraser, “The Spaces, Politics, and Cultural Economies of Electronic Dance Music,” Geography Compass 6, no. 8 (2012)

Douglas Wolk, “The Chemical Brothers Make a Triumphant Return After Five Years with ‘Born in the Echoes’: Album Review,” Billboard , July 20, 2015

Kat Bein, “Armin van Buuren Finds a New Groove with Conrad Sewell, Scott Storch,” Billboard , February 2, 2018

David J. Hoek, Steve Reich: A Bio-Bibliography (Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Press, 2002)

Sean Albiez and David Pattie, eds., Brian Eno: Oblique Music (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2016)

External Links:

"Electronic Dance Music" (Encylopaedia Britannica)

The Chemical Brothers Official Website