Summary:

Chapter 14 is the sixth of seven chapters dedicated to one of the key “genotypes” presented in this book: that dedicated to world music. The chapter begins with a brief etymological and stylistic gloss of world music, along with an offering of ten reasonable touchstones for this species. It then proceeds to the main thrust of the chapter: the unwinding of the historical and then musicological details behind the five “hits” for Subject 6, a devotee of the world music species. These five (four in the book, one on the website only) are: Cheb Mami’s “Youm Wara Youm”; Youssou N’Dour’s “Birima”; Hamza El Din’s “Assaramessuga”; Afro Celt Sound System’s “Release”; Ravi Shankar’s Morning Love . The chapter closes with a range of potential candidates for addition / future hits for Subject 6, based on proximity on various levels to the five seeds.

Supplements:

- Page 513

( Presentation of 5th “hit” discussed for Subject 6: Afro Celt Sound System’s “Release” ):

The following is the full discussion of the 5th song of the world music genotype, Afro Celt Sound System’s “Release”, heard on the way home from work. It was excluded from the main text and delimited to the website only:

A Night Club High-Note: Afro-Celt Sound System’s “Release”

Afro-Celt Sound System’s “Release” resumes a rather more conventional account of world music—a collaboration between an eclectic “world fusion” band and an eccentric Irish rocker, Sinéad O’Connor. Such might make us wonder if the more traditional discourse heard in the el Din was but a genotype anomaly…

Background

Simon Emmerson, a London-based guitarist, founded Afro-Celt Sound System (ACSS) in 1995 following a recording session with West African singer Baaba Maal. A celebrated singer / guitarist from Senegal, Maal has pursued a quite different musical terrain (based on the yela genre) than fellow countryman Youssou N’Dour.[1] During the session, Emmerson noted the similarity in melodic style between a traditional West African song and some Irish airs he knew, and had a crazy notion: to combine West African and Celtic musical practices into a single ensemble. Recruiting a pair from Maal’s band, some traditional Irish musicians he knew, and some EDM artists to capture the London club scene, ACSS was born.

The band was immediately signed to Peter Gabriel’s Real World Records label, for which it released 6 albums between 1996 and 2005. All have been both critically and commercially successful—including the 1999 gold record Volume 2: Release .

Gabriel himself has been a forceful advocate of world music going back to at least 1980, when he co-founded the World of Music, Arts, and Dance (WOMAD) Festival; this series of concerts and workshops combines Western and non-Western artists, and is still going strong today. Real World Records, formed in 1989, became an obvious complement to the festival, with a roster that includes Pakistani Quawwali singer Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, the Turkmenistan ensemble Ashkhabad, the Creole Choir of Cuba, and the Blind Boys of Alabama, to name a few. ACSS has been the label’s biggest seller after Gabriel himself. Moreover, Gabriel has collaborated as a singer/composer with dozens of “world” musicians, including Youssou N’Dour, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Brazilian singer Milton Nascimento, and ACSS—notably on their 2001 hit, “When You’re Falling”. In so doing, Gabriel stands prominently among a small list of rock icons—including Paul Simon, Sting, Bob Geldof, Bono, and George Harrison—who have helped introduce millions of listeners to world music practices that they otherwise may have never known.

Analysis

“Release”, the title track from the group’s 1999 sophomore album, arose in response to a tragedy that befell the band. Just prior to beginning recording, their keyboard programmer, Jo Bruce (son of Cream drummer Jack Bruce), died suddenly of an asthma attack, leaving the band devastated. During an impromptu session, O’Connor contributed vocals to a then-incomplete track, wherein she channeled the spirit of their recently departed colleague with new lyrics: “Don’t think you can’t see me…” Her healing participation enabled the band to complete the song and the album—which went on to become their biggest seller.

In their own words, ACSS makes no attempts to produce authentic music of any particular region—whether West African or Irish (Celtic). Rather, the inherent mastery that the participating musicians have of their respective traditions is brought into an intentional cross-cultural exchange to produce something entirely new. “Release” is a prime example: the track combines the tama (talking drum), the djembe (frame drum), uilleann pipes (Irish bagpipes), Irish whistle, hurdy gurdy, accordion, balafon (West African xylophone), Irish harp, synthesizers, electric bass, drums, and vocals in English, Irish Gaelic, and Malinke (a common West African language) into a kind of musical smorgasbord. From a listening experience standpoint, therefore, diversity in texture and sonority become the prime points of focus, quite apart from the elements that bind them together.

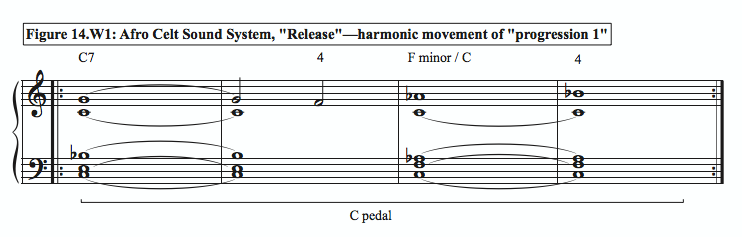

The elements that do bind them, however, are musicologically quite simple and straightforward. Key among them is the use of a sustained drone or pedal point—as noted, a staple of musical traditions around the world. Following the subtle rise of Eno-esque ambient synth sounds, a tempo-less tama solo begins just as a mid-range C pedal point starts to emerge. Once established, it will remain throughout the rest of the 7:36 track. The djembe and rock drums soon lock into a medium 4/4 groove—part African, part drum and bass—as N’Faly Kouyate, the band’s Guinean griot, recites in Malinke. At 1:17, the song “proper” begins with the establishment of a harmonic movement above the C pedal: a 4-bar pivoting progression from C7 to F minor/C (2 bars each)—ornamented by an atmospheric melodic line: G-F-Ab-Bb. This will be the first of three repeating chord progressions above the C drone that will provide harmonic movement and variety to the track (Figure 14.W1):

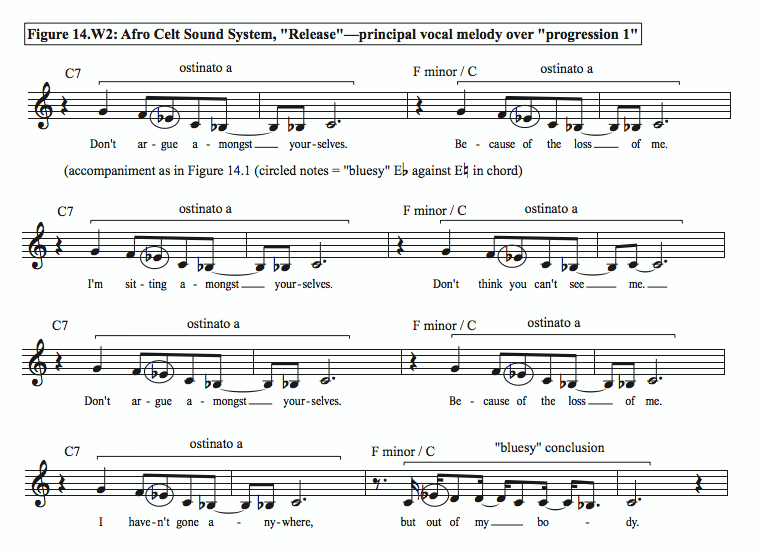

O’Connor introduces the song’s main vocal melody (1:38)—less a melody in fact, than a 2-bar ostinato that repeats successively 7 times before altering to a cadence that reinforces its overall “bluesy” nature (Figure 14.W2):

O’Connor’s melodic ostinato continues to repeat as the track introduces the 2nd chord progression: a dramatic push beyond the two chords of “progression 1” to Amin/C—C11, thus creating an internal melodic ascent of G-Ab-A-Bb. These two chord progressions then cycle back around to accompany vocalist Iarla O’Lionáird as he sings a variant of O’Connor’s melody, with lyrics in Irish Gaelic. O’Lionáird, in fact, quickly varies away from O’Connor’s ostinato, in an expressive contour that culminates with another repeating ostinato set over “progression 2” (Figure 14.W3):

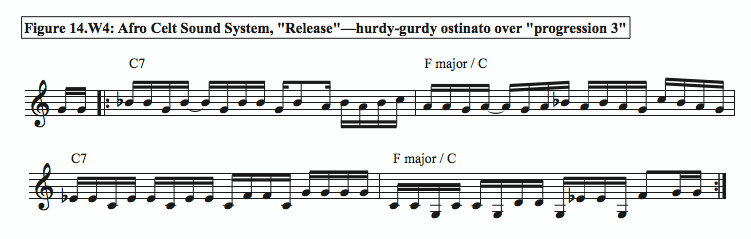

The third repeating harmonic progression—C7 to F/C (1 bar each, creating an internal melody of Bb-A)—arrives in support of the first of a set of instrumental solos: uilleann pipes (3:52), joined by Irish whistle (4:02); Irish whistle solo against progression 2 (4:11); and hurdy gurdy against “progression 3” (4:35). In each case, the solos are not improvisatory, but built upon short ostinatos of 1 or 2 or 4 bars in length—such as this one by the hurdy-gurdy (Figure 14.W4):

The prevailing use of melodic ostinatos is the second musicological element that binds the disparate sonic elements of “Release”. After the hurdy gurdy solo, the remainder of the song is largely a reprise and reassembly of the various ostinatos—vocal and instrumental—heard before. A striking moment (at 5:14), for example, is the complex layering of O’Connor’s vocal ostinato, the hurdy-gurdy ostinato, and the uilleann pipes ostinato, all locked in groove with active drumming, a funky bass line, and the hypnotic C7-F/C drone-based pivot of “progression 3”.

Indeed, it is the three drone-based pivoting progressions that ground the ear, and in turn enable this rich contrapuntal layering of ostinatos. These two elements together anchor the trance-like effect that sonically defines the song—to which the various and exotic instruments, timbres and vocal languages add color and detail. The ostinatos noted above are not the only ones in this dense soundscape, moreover; they likewise appear in the balafon, the Irish harp, the electric bass, and vocal chants in Gaelic and Malinke, amidst a variety of synth and keyboard sounds. The result, again, is a “world fusion” mélange that sounds neither African nor Celtic, yet strangely both—and which clearly provides ample sonic stimulus for Subject 6.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] For more background on both Baaba Maal and the Afro-Celt Sound System, see their biographies on the All Music and Wikipedia websites; see also Broughton. World Music , Vol. 1: 178.

- Page 532

( More on the gharana or “music school” system in India ):

The gharana system of musical apprenticeship dates back to the Mughal invasion in the 16th century, where each “school” was patronized by the local prince—not unlike the cappella system in the West.

- Page 533

( More on the Shankar’s introduction of Morning Love to flutist Jean-Pierre Rampal ):

That is, Shankar performed Rampal’s part live, from whence it was transcribed for the flutist to subsequently read.

- Page 534

( A more detailed listing of the timings of each individual section of Morning Love ):

To help orient the more diligent listeners among you, Table E.W1 lists the timings for each formal sub-divisions noted above—including the many exchanges between Gat “refrains” and “episodes”:

| Table E.1: Morning Love —Structure and Timing

Alap Alap, Part 1 (sitar) = 0:11 Alap, Part 2 (flute) = 1:34 Jor = 2:39

Interlude 1 (introduction to Gat – tabla solo) = 3:40

Gat (Part 1): Refrain 1 = 4:24 Refrain 9 = 8:27 Episode 1 = 4:42 Episode 9 = 8:32 Refrain 2 = 4:54 Refrain 10 = 8:36 Episode 2 = 5:07 Episode 10 = 8:40 Refrain 3 = 5:28 Refrain 11 = 8:44 Episode 3 = 5:35 Episode 11 = 8:46 Refrain 4 = 6:10 Refrain 12 = 8:48 Episode 4 = 6:22 Episode 12 = 8:50 Refrain 5 = 6:39 Refrain 13 = 8:52 Episode 5 = 6:51 Episode 13 = 8:54 Refrain 6 = 7:36 Refrain 14 = 8:56 Episode 6 = 7:48 Episode 14 = 8:58 Refrain 7 = 8:04 Refrain 15 = 9:00 Episode 7 = 8:15 Episode 15 = 9:02 Refrain 8 = 8:19 Refrain 16 = 9:08 Episode 8 = 8:24 Episode 16a = 9:10

Interlude 2 (tabla solo) = 10:16

Gat (Part 2): Episode 16b (Thematic variation) = 11:05 Refrain 17 = 11:36 |

Principal Bibliography:

Philip V. Bohlman, World Music: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2002)

Ian Birrell, “The Term ‘World Music’ Is Outdated and Offensive,” Guardian , March 22, 2012

Andrew Hammond, Pop Culture Arab World!: Media, Arts, and Lifestyle (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2005)

Hana Noor Al-Deen, “The Evolution of Rai Music,” Journal of Black Studies 35, no. 5 (2005)

Jon Pareles, “Youssou N’Dour Performs at the Brooklyn Academy of Music,” New York Times , September 14, 2014

Jon Pareles, “Hamza El Din, 76, Oud Player and Composer, Is Dead,” New York Times , May 25, 2006

Reginald Massey and Jamila Massey, The Music of India (New Dehli: Abhinav Publications, 1996)

Ravi Shankar, Raga Mala: The Autobiography of Ravi Shankar (New York: HarperCollins, 1999)

External Links:

"World Music" (Encylopaedia Britannica)

Afro Celt Sound System Official Website